Senior advocate Harish Salve is assisting the 50-lawyer strong society of Indian lawyers fighting the Bar Council of India (BCI) in the Supreme Court, for liberalisation in Indian legal services.

More than one year after several foreign law firms dropped out of the case, the Global Indian Lawyers Association (GILA) yesterday intervened in the BCI’s appeal against the Madras high court’s decision in AK Balaji V Union of India, and filed a separate petition challenging the Bombay high court’s six-year-old decision in the Lawyers Collective case, which upheld the entry of foreign law firms.

The petition by GILA challenging the Lawyers’ Collective judgment drew on the advice of senior advocate Harish Salve, who is involved in the matter on a pro bono basis for the society.

Salve “settled” GILA’s intervention application and SLP, according to a source with knowledge of the matter. The source explained that “a senior counsel of eminence [such as Salve] settling a petition, i.e. reading, discussing and adding his own thoughts to it”, was a rare occurrence.

Senior advocate Huzefa Ahmadi appeared, also pro bono, for GILA in the Supreme Court yesterday, after Salve could not make an appearance due to commitments in Bombay, explained the source.

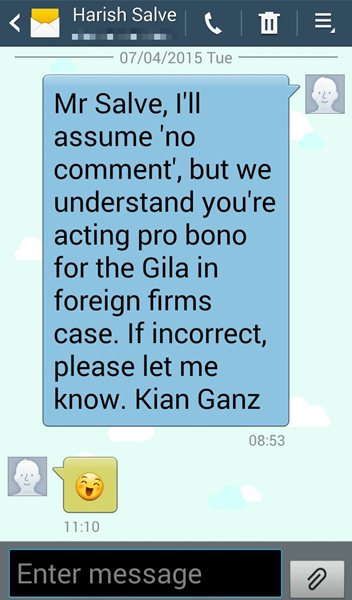

Salve, who was being fast-tracked to join the English bar and practises as a barrister in London’s prestigious Blackstone Chambers part-time since 2013, did not respond to messages seeking comment since yesterday.

Salve told Legally India in 2013 that Indian opponents of liberalisation had been “fed misinformation” and that the entry of foreign lawyers would be the “best thing for young Indian lawyers”.

Unexpected bedfellows

GILA was formed around eight months ago by young dual-qualified Indian lawyers practicing in Indian courts or with Indian law firms, but having foreign law degrees as well.

GILA president Pradhuman Gohil told Legally India that the society was interested in the rights of its own members to practice foreign law in India, and was not really espousing the cause of foreign law firms wanting to gain entry to the Indian legal market.

Gohil, who practices in the Supreme Court, said: “All the members [of GILA] are either dually qualified or have LLM degrees from abroad. So we thought that why can’t we practice foreign law here, if at all we are eligible to practice foreign law?”

“If foreign law firms are allowed to come and practice here it is not necessary that the foreign lawyers need to do an LLB to practice here. The basic idea [behind our challenge] was that [currently] Indian lawyers go abroad and start working there, [but] it is much better to have a proper environment here in India. Why should we go to another country if at all we can stay in India and we can practice foreign law?” he added.

The unnamed source added: “The way BCI is approaching it is from the perspective of foreign lawyers who have come to India and [want to] practice. Now if a foreign lawyer comes to India and practices, frankly all he is doing is foreign law.”

“But today there is an India practice which is set up in all these foreign law firms. It is actually staffed by Indian lawyers. So why do you have a brain drain where you have people from India going and working with Herbert Smith, Freshfields, Clifford Chance and all that when they’re all Indian qualified, they are dual qualified. Why can’t they sit in India and do their own practice?”

Commenting on GILA, the source added: “Their only aim is to give notice to the Supreme Court that if you take such a myopic view of the matter as the bar council wants you to do then you are not giving young Indian lawyers an opportunity of practising with the best in the world.”

The petition & arguments

GILA challenged the 16 December 2009 judgment in Lawyers Collective after a delay of 1,826 days, stating in its SLP that in its 2009 judgment the Bombay high court “erroneously held that to practice the profession of law in India, a foreign law firm has to fulfil the qualification of being enrolled as advocates under the Advocates Act 1961”.

The petition states that the judgment, in its “incorrect reading of the concept of a law firm”, “erroneously places a qualification on foreign firms to register as advocates under the Advocates Act, when there is the no such restriction under the Advocates Act or under the Bar Council of India Rules (the "BCI Rules") to prohibit a foreign law firm from establishing an office in India”.

It asserts that the Advocates Act requires only individual lawyers to be registered as advocates in India, and law firms which are only a collection of such individually registered lawyers, need not register in India. Indian law firms currently established in India are not so registered, and foreign firms need not also be.

The petition also draws attention to issues which it states were not touched by the Madras high court in the AK Balaji case:

1. An Indian qualified lawyer can qualify in multiple jurisdictions and there is no restriction on such Indian qualified lawyer from practicing Indian law as well as the law of the other jurisdiction(s) where he or she has qualified.

2. The requirements under the Advocates Act and the BCI Rules for registration of lawyers based upon the demarcation of the practice of the profession of law into the practice of Indian law and the practice of foreign law.

3. the possibility of whether a foreign law firm could have Indian qualified lawyers join the firm and practice Indian law, whereas the foreign lawyers could practice only foreign law.

4. there is no restriction in the Advocates Act or the Bar Council Rules for profession of foreign law in India by appropriately qualified lawyers on [not just fly in fly out basis but] a permanent basis as well (such lawyer could be a dually qualified Indian citizen as well).

5. The Advocates Act and the BCI Rules do not regulate or prohibit the profession of foreign law, which is governed by laws of each foreign state and only apply to the practice of Indian law.

6. The work conducted by foreign law firms in India would not go unregulated as each individually registered lawyer part of such firms would be regulated by the Advocates Act, as is the case with Indian law firms.

GILA filed its intervention and its SLP in the Supreme Court through advocate-on-record Vikas Singh.

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first

sabse sasta sunder tikau phoren llm kaun sa hai bhai ?

Though in theory, anything sent to a journalist, unless explicitly said to be off-the-record, should be considered to be for publication.

However, unless it's obvious I'm seeking a comment from a person on something, I usually treat personal messages and emails as off-the-record, though it also usually depends on the type of relationship a journalist has with a source.

And before any youngsters get scared - we never quote anything we get from students, associates or younger partners unless it's obvious we're asking for their comment on something, and if you don't want to be quoted in any case, you can just preface whatever you write to us with off-the-record.

Though I guess when you've reached the level of Salve or a RamJet, you can afford to be fun. :)

Here's something topical along similar lines: www.wired.com/2015/03/google-sends-reporter-gif-instead-no-comment/

Am waiting for the first lawyer to send us a gif, when we next ask them for comment... (Yes, this is an open invitation :)

twitter.com/hsalve/status/585444196300926976

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first