In the history of political parties in India, the rise and fall of Janata Party must form an important chapter.

The party had captured power at the Centre in the aftermath of the lifting of the Emergency in 1977. Soon after, in 1980, it lost power and began to disintegrate, with many leaders and followers leaving the party at various phases.

But one person clung on to the party and its symbol for a very, very long time, surprising many observers. He led the party with its various state units all alone since 1990, and fielded candidates in every election on behalf of the party.

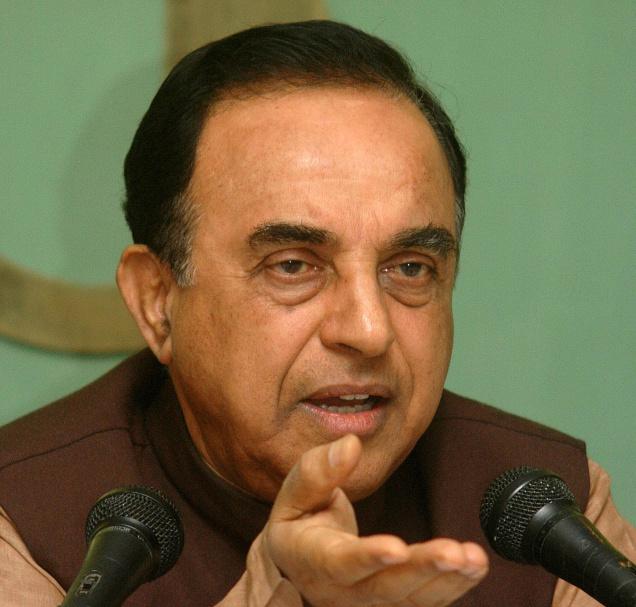

He was Subramanian Swamy, the maverick political leader, who had waged many one-man battles against corruption, and against leaders who were alleged to have indulged in corruption.

Some newspapers continued carrying stories describing him as president of the Janata Party, even though the party had virtually no presence anywhere anymore.

On 11 August 2013, the Janata Party formally merged with the BJP, thus finally bringing the curtain down on its history.

It now appears that part of the reason why Swamy might have decided to abandon his crusade as president of the Janata Party must have had to do with his travails of fighting an income-tax case on behalf of the now-defunct Janata Party, for its handling of finances during the period, when he was the president.

A bench comprising Justices S Muralidhar and Vibhu Bakhru of the Delhi high court, on 23 March, indicted Swamy and his auditor for producing accounts that could not enable the Assessing Officer to properly deduce the income of the Janata Party.

The bench held that the consolidated accounts produced after the filing of the returns disclosed a figure of voluntary contributions to the party that differed from that disclosed in the return.

The consolidated returns revealed the figure of voluntary contribution in the sum of Rs 1,17,10,370.

The entries in the bank accounts, as also in the ledger produced in respect of the central office, showed that there were donations of more than Rs 10000. Yet, in order to substantiate its stand that the individual contributions were less than Rs 10000, the assessee submitted manually numbered receipts, which were rightly disbelieved, the high court noted.

The bench found that Swamy’s claim that all donations were received in cash, were accumulated at the various units and were remitted to the central office personally by the party functionaries when they happened to visit New Delhi was not substantiated.

The assertion that each donation was less than Rs 10000 was a desperate one and not at all convincing, the bench observed.

A political party which seeks to avail of the exemption from paying income tax under Section 13A of the Income Tax Act, cannot be heard to say that it is not possible for it to maintain its accounts on a consolidated basis, the bench added.

The bench found the clean chit given to Swamy by the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal (ITAT) as perverse and contrary to evidence on record, in so far as the applicability of Section 13A of the Act is concerned. The Revenue department had challenged the decision of the ITAT before the high court.

The result of the high court judgment is that the ITAT’s order dated 23 November 2001 has been set aside and the order dated 31 March 1998 of the Assessing Officer, as upheld by the order dated 16 February 2000 of the Commissioner of Income Tax (A), was restored.

It appears Swamy’s travails with the income tax department, despite the merger of Janata Party with the BJP, are likely to continue in view of the setback he received in the high court case.

Congress is equally guilty

The bench’s decision in Swamy’s case has been released simultaneously with a similar decision in the appeal filed by the CIT-XI against the Congress party, which went against the latter.

The Congress claimed exemption from paying income tax for the Assessment Year 1994-95, while the Janata Party had claimed similar relief for the AY 1995-96.

The bench held that the Congress was not entitled to claim exemption from paying income tax for the AY 1994-95 since it failed to maintain properly audited accounts.

The bench observed in Paragraph 119 that there is a lacuna in the Income Tax Act inasmuch as upon failure of a political party to comply with the Act in letter and spirit, and with auditors not discharging their statutory obligation, the income tax authority is hamstrung by the lack of reliable data on which to base a reasonably accurate estimation of income of a political party.

Importantly, the bench held that a political party is not a charitable trust, and therefore, it would serve no purpose to compare it with Section 11 of the Act, which applies to trusts. Secondly, it held that income by way of voluntary contributions would be excluded only subject to fulfillment of the conditions stipulated under Section 13A of the Act.

The conditions include maintaining books of accounts, keeping a record of voluntary contributions in excess of Rs 10000 (now enhanced to Rs 20000) and getting the accounts properly audited. If these conditions are not fulfilled, the income of a political party by way of voluntary contributions would be included in the taxable income, the bench held.

In the concluding paragraph, the bench observes that the proper auditing of the accounts of political parties is critical to the conduct of free and fair elections, as they deal in large sums of public money, much of which is unaccounted. The bench, therefore, endorsed the recommendations of the Law Commission, as carried in its 255th Report, submitted in March 2015.

Among the significant changes recommended by LCI is that “only upto Rs 20 crore or 20 per cent of the total contribution of a political party’s entire collection (whether cash/cheque), whichever is lesser, can be anonymous. Apart from this, the details and amounts of all donations and donors (including PAN cards, wherever applicable) need to be disclosed by political parties, regardless of their source or amount.”

The bench held that the LCI’s recommendations should receive serious and urgent attention at the hands of the executive and the legislature if money power is not to be allowed to distort free and fair elections.

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first