When the Department of Electronics and Information Technology (DeitY) published the Draft National Encryption Policy last week, it probably did not expect to have it withdrawn in just a few days' time. After facing a seething attack from all quarters, the IT Minister, Ravi Shankar Prasad, announced that the draft policy was not the government’s final view, and a revised policy would soon be published.

The government’s decision to open up the draft policy for public consultation is a positive step towards promoting information security in India.

There is an urgent need to introduce a uniform policy to replace the hodgepodge of encryption standards applicable to the banking, finance and telecom sector.

If carefully drafted, a National Encryption Policy would help safeguard the privacy of individuals, ensure that Indian businesses are competitive in international markets, and protect government departments against cyber attacks. Unfortunately, the draft policy failed on most counts.

Why is encryption important?

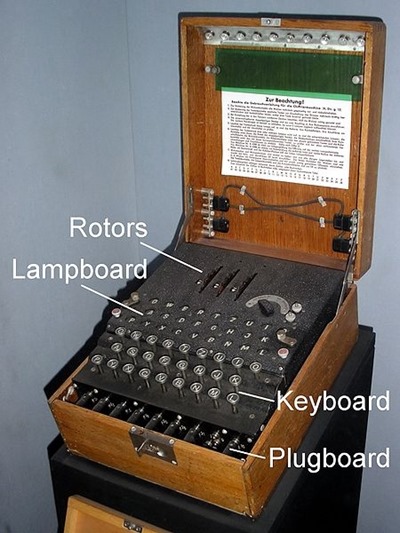

Encryption is the process by which information is modified so that only authorised parties can read it. It helps:

(1) prevent others from intercepting and reading messages; and

(2) verify the identity of the sender.

Perhaps think of it as a letter written in code so secret and complex that only the intended recipient can ever understand it, delivered in a lockbox sealed in wax with your unique signet ring. Only better, because there is maths involved that's so sophisticated it's almost magical.

Banks use encryption to keep credit card details secret, (a few) lawyers to communicate with clients, journalists to chat “off the record”, and criminals to plan crimes.

Like most technology, encryption is a double-edged sword.

Encryption became a buzz word after Edward Snowden revealed that the United States government spied on its citizens, in part by intercepting data flowing between web companies' servers (in response, Google rushed to encrypt such traffic). These developments, coupled with data breaches of websites such as Ashley Madison and Sony's, highlight the need for information security through encryption.

What do other countries do?

Many countries have adopted policies to regulate how encryption is used in a variety of manners, though it's fair to say that all countries have struggled to understand and control the technology.

While the US constitution has safeguarded the free use of encryption in the US, some export controls for encryption tools still exist, and until 2010, most higher-grade encryption technology was prohibited from being exported outside the US as “auxiliary military equipment”.

The UK has the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) 2000. While not banning the use of encryption, it allows the government to force you to provide the decryption keys to any encrypted information in your possession in certain circumstances, or face imprisonment if you refuse. South Africa and Australia have similar provisions.

In India, section 69 of the Information Technology Act, read with the Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009 could also be used to force the decryption of information.

So why does India need more law on encryption?

The objectives of India's National Encryption Policy appear to be sound—to encourage the adoption of best practices that are consistent with industry practice, to ensure the privacy and security of information.

But the government seems alarmingly out of touch with how encryption technology is used in today’s hardware and software. As a result, the draft policy published by DeitY put users at risk by disregarding industry best practices and pushing for greater government control.

Restricting user choice and privacy

According to the draft policy, Indian citizens would only have been able to use encryption products registered in India. A compulsory registration system of this nature would have restricted Indians from using several helpful tools to secure their communications, including The Onion Router (TOR), virtual private networks (VPNs) and Pretty Good Privacy (PGP).

The draft policy required individual users to store encrypted data in plain text for at least 90 days, and to hand over such data to authorities when demanded. In a clarification issued a few hours before the policy was withdrawn, the government exempted "mass-use encryption products" (such as SSL/TLS) that are widely used in social media, internet banking and e-commerce transactions.

But practically speaking, this provision would have nevertheless been a death-knell for secure messaging services like Telegram and devices like the Blackphone, which are designed to protect sensitive communications. They purport to leave no trace of messages on servers, support self-destructing messages and disable forwarding of messages.

Though widely used by journalists, lawyers and activists around the world, particularly those working under the more repressive regimes, such services would probably be illegal under India’s proposed encryption policy.

Is the Indian government perhaps struggling with new technology?

It's not the first time actually…

The Indian government has a long history of prescribing unreasonable encryption standards.

For example, under existing telecom regulations, users of internet services cannot use encryption above 40 bits in key length without the government's prior permission – akin to using a cheap padlock to secure your lockbox with your letter inside.

If stronger encryption is used, the IT ministry's 2007 guidelines technically require that a copy of the decrypt key be left with the government so they can open and read your messages whenever they like.

Globally recommended encryption standards, even for basic web browsers, are much higher than 40 bits. Mandating a low threshold is bound to clash with standard protocols that are used to encrypt data around the world, rendering Indian standards practically unenforceable.

The big concern is that the government seems determined, albeit clumsily, to have the ability to penetrate the most intimate details of our lives, even offline.

Encrypting personal devices such as USB drives and smartphones, which until now was considered a prudent precautionary measure against thieves or hackers, would suddenly be subject to government scrutiny and penal sanctions.

For law-abiding citizens who enjoy tinkering with technology as a late-night hobby, such policies impose additional restrictions without any basis in fact or law.

Anti-innovation

The National Encryption Policy, in its initial form, would affect both start-ups and global players operating in India. The proposal for registration of encryption products and services is akin to the demand for licensing of internet services. It is simply not conducive to doing business.

Consider the case of Indian start-ups that rely on foreign data centres. The draft policy states that the primary responsibility for complying with law enforcement requests falls on the entity that is based in India, and not the foreign service provider. This might push Indian entrepreneurs to incorporate their businesses in Singapore, and use cloud services from countries with advanced data sharing regimes.

Under the draft policy, all businesses that use encryption technology in existing services would also have to sign an agreement with the government.

In a post-Snowden world, that is a long list – including operating systems, enterprise software, routers, web-browsers etc. And although the SSL/TLS protocol comonly used by web browsers for internet banking and e-commerce was later exempted, the draft policy would not have addressed the use of other common standards, now or in the future.

The government has much to lose by enforcing something like the National Encryption Policy in its latest form given that the ‘Make in India’ campaign relies heavily on domestic manufacturing and export of electronic products.

The proposed registration process and export restrictions would dampen the chances of achieving ‘Net Import Zero’. Software companies that provide IT/ITeS services to the government may also be reluctant to participate in future bids if RFP’s contain incompatible encryption standards, or if the National Encryption Policy was used to advance preferential market access.

Law enforcement access

Many of the repugnant provisions in the draft policy exist to facilitate government monitoring and interception of communications. At a time when revisions to the encryption policy are being considered, it is important to discuss specific concerns around law enforcement access, while being mindful of industry best practices around information security.

This is very important. There is good reason to believe that the 2008 Mumbai attacks involved the use of encrypted devices. It is also true that internet companies are sometimes slow to respond to information requests, putting the lives of police officers and civilians at risk.

But the solution cannot be to simply make encryption redundant. Instead of designing backdoors into existing applications, the focus should be on improving data sharing mechanisms, reforming Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLAT), developing standardised formats for law enforcement requests and compelling businesses to publish granular data in transparency reports.

What now?

The Draft National Encryption Policy, despite its flaws, is a necessary beginning.

In order to achieve its stated objectives, a revised policy is essential. But at least three steps must be initiated in parallel –

(1) training programs in cryptography for government officials, and tutorials for interested users;

(2) improving data sharing mechanisms, including the MLAT; and

(3) ensuring necessary and proportionate penalties for individual users in case of non-compliance

Encryption, at its basic level, is a math problem. But the proposed National Encryption Policy opened a can of worms by striking at the heart of peer-to-peer communications.

It affects not only banking institutions and telecom service providers, but also the average user and budding entrepreneur.

In the interest of national security and individual liberty, government agencies must work closely with businesses to ensure that its own citizens do not suffer from imperfect systems designed for law enforcement and intelligence gathering.

Amlan Mohanty is a lawyer and policy consultant based in New Delhi. All views expressed in this article are personal.

Photo via Wikipedia page on Enigma

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first