Data privacy is a burning issue, from the Aadhaar ID database to a series of recent government and judicial reports laying the groundwork for a much-overdue reform of Indian privacy regulations, which will affect a plethora of businesses.

Impact will be felt by a wide range of industries, in particular internet companies, the data that the Internet of Things will collect, global IT services players based in India and sectors such as pharmaceuticals, where generation and storage of personal data is at the heart of paid-for clinical trials in India, potentially going right down to someone’s DNA. The question of where the lines of consent will be drawn will be fundamental.

And while some of the implications of technology on privacy are nearly impossible to foresee today, the concerns of national security are also likely to cast a major shadow on the legislation.

On 24 August 2017, the Supreme Court in the Puttaswamy case (see box) said that privacy was a fundamental right protected under the constitution; meanwhile on 31 July 2017, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, Government of India framed the terms of reference for a committee under the chairmanship of Justice B.N. Srikrishna: (a) to study various issues relating to data protection in India; and (b) to make specific suggestions for consideration of the Central Government on principles to be considered for data protection in India and suggest a draft data protection bill.

Right to Privacy: Supreme Court in Puttaswamy

On 24 August, 2017, a nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court of India in the landmark decision in Puttaswamy1 unanimously ruled that the right to privacy is intrinsic to life and liberty and hence is a fundamental right grounded in both Article 21 and Article 19 of the Constitution, encompassing freedom of the body as well as the mind. The major highlights of the decision were:

- Privacy is intrinsic to and inseparable from human element in human being.

- Right to Privacy is not just a common law right but a fundamental right guaranteed by Part III of the Constitution.

- Privacy is not an absolute right, subject to permissible restrictions.

- Action must be sanctioned by law, it must be necessary to fulfil a legitimate aim of the State and the interference must be ‘proportionate to the need for such interference’.

- Recognition and enforcement of claims for breach qua non-state actors will require legislative intervention by the State.

The Justice Srikrishna Committee’s White Paper of the Committee of Experts on a Data Protection Framework for India (the “White Paper”) was delivered in November 2017, and raises several critical issues for consideration.

Historical blind spot

While privacy and data protection has seen far less attention in India than in Europe or the US, for instance, in 2012, the erstwhile Planning Commission of India had constituted a committee under the chairmanship of Justice AP Shah to deliberate and analyse the national privacy principles in light of emerging issues both in India and globally.

Justice Shah’s report floated a framework highlighting the following that Indian data protection regulations required:

1. Technological neutrality and interoperability with international standards;

2. Multi-Dimensional privacy;

3. Horizontal applicability to state and non-state entities;

4. Conformity with privacy principles; and

5. A co-regulatory enforcement regime.

But it was not until the Aadhaar national identity database was challenged in court by nonagenarian retired Karnataka high court judge Justice KS Puttaswamy and others, that a more substantive debate began taking place.

On 9 August 2017, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (“TRAI”) released a consultation Paper on Privacy, Security and Ownership of the Data in the Telecom Sector2 for stakeholders’ comments. The aim of the paper was to identify the key issues pertaining to data protection in relation to the delivery of digital services. TRAI, in its consultancy paper, had sought comments from the public on twelve separate questions – they range from the definition and ownership of the personal data to regulation and audit of data controllers to balancing of rights of each stakeholder to the issue of cross-border flow of information.

To date TRAI has received 53 comments and 12 counter-comments from different stakeholders in the value chain. Though the consultation was open to the public at large, most comments were received from the Telecom Service Providers (“TSP”), over-the-top (“OTT”) content providers and the industry associations. We have referred to the comments whenever relevant.

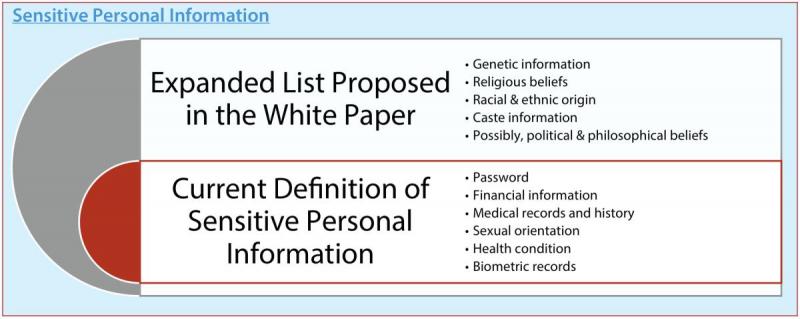

Today the main enactment that deals with protection of data is the Information Technology Act, 2000 (“IT Act”) and the Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal information) Rules, 2011 (the “IT Rules”). Personal information is defined under Rule 2(i) of the IT Rules to mean “any information that relates to a natural person, which, either directly or indirectly, in combination with other information available or likely to be available with a body corporate, is capable of identifying such person”.

It is noteworthy that, at present, only sensitive personal data (a sub-set of personal data) is protected under the IT Act and the IT Rules. Rules 5 of the IT Rules prescribes that no body corporate shall collect sensitive personal data or information unless (a) the information is collected for a lawful purpose connected with a function or activity of the body corporate; and (b) the collection of such information is considered necessary for that purpose. Rule 6 of the IT Rules prescribes that no body corporate can disclose sensitive personal information to any third party without permission from the provider of such information.

The Justice Srikrishna White Paper

The White Paper that Justice Srikrishna and 8 other experts on data and privacy laws from different domains produced, proposed that data protection laws should provide protection to the entire gamut of personal data with a higher level of protection to sensitive personal information than personal data and a more stringent penalty be imposed for harm/ breach of privacy law involving sensitive personal data. The White Paper has proposed an expanded list of personal data to be categorised as sensitive (see graphic below).

The 243-page White Paper addressed seven main themes:

1. Technology agnosticism – The law must be technology agnostic. It must be flexible to take into account changing technologies and standards of compliance.

2. Holistic application – The law must apply to both private sector entities and government. Differential obligations may be carved out in the law for certain legitimate state aims.

3. Informed consent – Consent is an expression of human autonomy. For such expression to be genuine, it must be informed and meaningful. The law must ensure that consent meets the aforementioned criteria.

4. Data minimisation – Data that is processed ought to be minimal and necessary for the purposes for which such data is sought and other compatible purposes beneficial for the data subject.

5. Controller accountability – The data controller shall be held accountable for any processing of data, whether by itself or entities with whom it may have shared the data for processing.

6. Structured enforcement – Enforcement of the data protection framework must be by a high-powered statutory authority with sufficient capacity. This must coexist with appropriately decentralised enforcement mechanisms.

7. Deterrent penalties – Penalties on wrongful processing must be adequate to ensure deterrence.

Exemptions from Data Protection Laws

The IT Rules currently in force only allow sensitive personal data to be collected by companies if:

the information collected for a lawful purpose

the collection of such information is necessary for that purpose.

The White Paper proposes to increase the scope of the categories of information that deserves exemption from data protection laws to include household purposes (i.e. information collected for an individual’s own use), journalistic/artistic, literary, academic research, statistics and historical purposes.

Out of the TRAI stakeholders commenting on its consultation, the Broadband India Forum suggested that private data should only be shared without consent for academics or other researchers for public value.

What is a Data Controller or Data Processor, and who is responsible?

Stakeholders consulted by TRAI have said that distinguishing between who is a data controller and data processor is important, in order to identify who is responsible for any data breach. Some believe that data controllers should primarily be responsible for complying with the law, though likewise, data processors should be responsible to take the necessary technical and organizational measures to secure the data they process on behalf of the controller. TRAI stakeholders felt that the ‘controller-processor’ relationships are governed through contractual means and the law should not unreasonably intervene in these relationships.

Basing it approach in lines with the EU Model,3 the White Paper proposes that the data controller should be primarily responsible for compliance with data protection norms; while the data processor may be provided with some level of responsibility. Obligation for each should depend on what kind of processing activities are undertaken by data processors.

However, currently, the concepts of data controllers and data processors are not provided clearly under the IT Act or the IT Rules. The words “originator”4 and “intermediary”5 as defined under the IT Act are insufficient for the purpose of data protection law, and various major stakeholders have told TRAI in consultation that much stronger and more lucid definitions of these terms are required in law.

According to the White Paper, the competence to determine the purpose and means of processing may be the test for determining who is a ‘data controller’. On the other hand, a data processor is an entity that is closely involved with processing, which however, acts under the authority of the data controller.

The tricky subject of consent

Consent in data protection and privacy – in effect whether you can contractually waive you right to privacy – is a tricky subject. The US approach is very much consent-based, whereas the European Union (whose citizens’ data is more often than not stored by US companies) has gone for an approach more in line with privacy as a fundamental right that can not be signed away and the state can regulate it.

India’s Supreme Court in Puttaswamy held that privacy is a fundamental right, which includes informational privacy, recognising that an individual should have control over the use and dissemination of information that is personal. Since any unauthorised use of personal information would lead to an infringement of this right, consent must be taken for collection or processing of this information.

However, there are certain issues with collection of information even with consent, four of which are discussed by the White Paper:

Lack of Meaningful and Informed Consent The most popular means of seeking consent is through notice to the user by the organisation informing the user of the potential use and dissemination of such personal information. Quite naturally it is expected that the notice would provide a fair and truthful information of the potential use of the consent. However, quite often we do not see that in practice.

Standards of consent According to the White Paper there is a need to have different standards of consent (and information in the notice) based on the sensitivity the personal data.

Consent Fatigue With the rise of computing power data processing has become routine work and as a result of this the users are flooded with consent notices.

Lack of Bargaining Power According to the White Paper, at present most of the online services come with only “take it or leave it” option. There is no provision for negotiation and the user has to forego the services offered.

The White Paper notes that there is a necessity to provide additional protection to children; but opines that the age of consent for data protection law need not be that of 18 years. The TRAI stakeholders have proposed an age of 16 years for providing consent.

The White Paper recommends the mandatory use of notice for privacy management and seeking consent of the users. It envisages that a Data Protection Authority6 would provide detailed guidelines and code of practices to regulate form and substance of the notice.

Also, to combat consent fatigue, the White Paper has suggested that no consent is required in performance of contract, compliance with law, collection of information in situations of emergency, or other “legitimate interest”, as designated and guided by the Data Protection Authority.

TRAI stakeholders agree that user’s consent for use of its personal/sensitive information is absolutely necessary. However, the method of obtaining consent could vary. According to most Industry Associations and OTT players (viz: Internet Service Providers Association of India, zeotab, Citibank, etc) the user must be given a choice of either “opt-in” or “opt-out”.

According to the GSM Association, collection of consent is not always easy (and sometimes redundant because the consumers generally always agree to online consent forms) and companies can give a consumer certain control (without the need for consent) like dashboard or tools to “opt-in” or “opt-out”. However, most consumer associations (such as the Consumer Protection Association) believe that if sensitive information is involved then there should be explicit consent of the user.

The individual’s right over data

The White Paper recognises the right of individuals to have access to personal data stored by a third party, and to have the ability to correct such data, though reasonable fees may be charged for it. The right to be forgotten and the right to erasure – i.e., to require the deletion of old data about individuals on request – may be incorporated within the data protection framework, though it must have clear parameters provided by the regulator.

Additionally, the White Paper proposes that all the above rights should also be provided to the data already collected before the implementation of the prospective data protection law.

‘Pseudonymised’ vs ‘anonymised’ data

Anonymisation seeks to remove the identity of the individual from the data, while pseudonymisation seeks to disguise the identity of the individual from data. Anonymization irreversibly destroys any way of identifying the data subject. Pseudonymisation substitutes the identity of the data subject in such a way that additional information is required to re-identify the data subject.

Globally, in most jurisdictions, anonymised data falls outside the scope of personal data while pseudonymised data continues to be personal data. The White Paper has reserved its views on this and has sought stakeholder’s comments.

Data protection and the Government

According to the White Paper, the law should apply horizontally to data about natural persons processed both by public and private entities. However, limited exemptions may be considered for well-defined categories of public or private sector entities.

The Supreme Court in Puttaswamy has laid down a threefold requirement for State’s interference with fundamental rights. While the State may intervene to protect legitimate state interests:

there must be a law in existence to justify an encroachment on privacy, which is an express requirement of Article 21 of the Constitution,

the nature and content of the law which imposes the restriction must fall within the zone of reasonableness mandated by Article 14, and

the means which are adopted by the legislature must be proportional to the object and needs sought to be fulfilled by the law.

The White Paper has taken this into consideration and has proposed exemptions for the following information:

Information necessary for the purpose of investigation of a crime, and apprehension or prosecution of offenders;

Information necessary for the purpose of maintaining national security and public order.

In addition, the White Paper proposes a review mechanism to ensure that this exemption is not granted unreasonably.

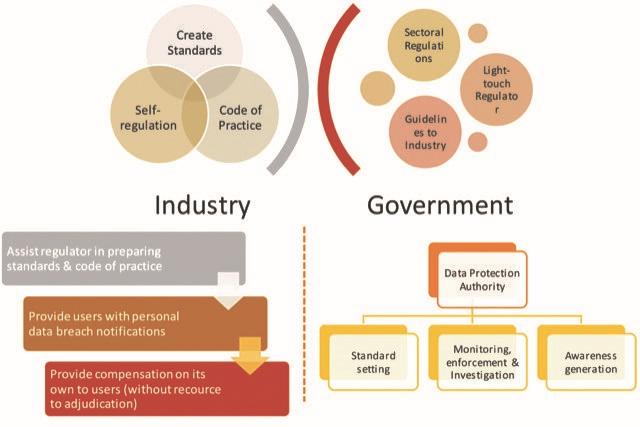

Enforcement frameworks: Co-regulation

The White Paper proposes a co-regulation model of enforcement. Co-regulation form of enforcement may be described as initiatives in which government and industry share responsibility for drafting and enforcing regulatory standards. Basic features of co-regulation model of enforcement are:

Formation of a general data protection statutes with broad provisions (eg: Industry Codes of Conduct)

Compliance with the detailed provisions of the Codes of Conduct would be indication of compliance with general provisions of the statutes

Since the issues pertaining to data protection is highly specialised the White Paper proposes to setup a separate and independent data protection authority at the national level with powers to (i) monitor, enforce & investigate; (ii) generate awareness; and (iii) setting of standards. The interface between the Industry and Government in a co-regulation model along with the role of the Industry and the Government is presented in a schematic format on the opposite page.

The White Paper has provided some detailed observations with respect to the adjudication process and has noted that the present adjudication framework is inadequate. The main feature of the proposed framework is that the aggrieved individual should approach the data controller first before approaching the Data Protection Authority with a complaint. Appeals could be made to the appellate tribunal formed under the IT Act. The White Paper also suggests that some actions would incur criminal liability; and where the investigation would be undertaken at a decentralised level (i.e. by a police officer not below the rank of Inspector).

While discussing the principles of harm and liability the White Paper identifies three types of harm to the user. Harm could be classified by loss of reputation, financial choice or limiting individuals’ choices. Liability in turn could either be triggered on i) proof of failure to take appropriate measures, ii) if the processing is inherently risky, the data controller is strictly liable, or iii) compulsory insurance to cover certain types of harm.

Information flows across border

The ease at which data can flow across jurisdictional border is both a matter of advantage and disadvantage. The fact that foreign entities need not establish local office for its operations would mean substantial lowering of operational cost which could then passed on to the consumers. On the other hand, it might be difficult to implement sanctions on these foreign firms because they are outside the jurisdictions of Indian laws. In the absence of any treaty or agreement cross-border implementation or enforcement of sanctions in most matters is generally guided by the principles of comity.7 However, that does not provide legal certainty.

The White Paper proposes that all entities, even those which do not have a presence in India, that offers a good or service to Indian residents over the Internet, or carries on business in India may be covered under the law. Additionally, in lines with EU GDPR, the White Paper proposes that any entity (no matter where they are located) that processes the personal data of Indian citizen or resident should be covered under the data protection law.

Enforcement of sanctions cross-border is an issue. The White Paper has suggested enforcement techniques such as mutual legal assistance treaties, restriction of access to the market, adopting penalties based on global turnover, and mandatory establishment of a representative office, holding Indian subsidiary/related entities liable for damages.

Data localisation would mandate companies to store and process data on servers physically located in national borders. The White Paper is of the view that only a few countries have adopted data localisation in some form or the other. It is of the opinion that while data localisation may be considered in certain sensitive sectors, it may not be advisable to prescribe it across the board.

About The Firm

Economic Laws Practice (ELP) is a leading full-service law firm, headquartered in Mumbai, India. The firm was established in the year 2001 by highly eminent lawyers from diverse fields who envisioned a firm that would bring to the table a unique blend of professionals, ranging from lawyers, chartered accountants, cost accountants, economists to company secretaries. The partners at ELP are not only knowledge leaders but thought leaders as well; enabling the firm to offer seamless cross-practice legal services, through top-of-the-line expertise to clients.

With 6 offices across India (Mumbai, New Delhi, Pune, Ahmedabad, Bangalore and Chennai), ELP has a team of over 170 qualified professionals. Working closely with leading national and international law firms in the UK, U.S., Middle East and the Asia Pacific region, gives ELP the ability to provide an extensive pan India and global service offering to our clients adding to the seamless service that the firm prides itself on.

ELP’s vision is people centric and this is primarily reflected in the firm’s focus to develop and nurture long-term relationships with our clients by providing optimal solutions in a practical, qualitative and cost efficient manner. The firm’s in-depth expertise, immediate availability, geographic reach, transparent approach and the involvement of senior partners in all assignments has made ELP the firm of choice for our clients.

ELP is firm of choice for clients due to our commitment to deliver excellence and has been ranked amongst the Top 10 firms in the country; with the highest Client Satisfaction score of 9/10 amongst the Top 10 firms as per RSG India Report 2015. The firm has also recently been recognised as Top Tier firm in India for Dispute Resolution, Antitrust & Competition, Project & Energy, Tax, WTO and International Trade by the Legal 500 Asia-Pacific 2017. “Highly Recommended” in 6 practice areas by IFLR1000 Financial & Corporate Guide 2017 and recognised by Asialaw Profiles 2017 as “Outstanding Firm for Tax”. Ranked in Chambers & Partners Asia-Pacific Guide 2017 for 9 practice areas.

Practice Areas

Banking & Finance Competition Law and Policy Corporate & Commercial Direct Tax, Indirect Tax, Tax Advisory & GST Infrastructure & Hospitality International Trade & Customs Litigation & Dispute Resolution Policy & Regulation Private Equity & Venture Capital Securities Laws & Capital Markets Telecommunication, Media & Technology.

Offices:

Mumbai, Delhi, Ahmedabad, Pune, Bengaluru, Chennai Tel: +91 22 66367000 | Email:

Footnotes

1. Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India & Ors. 2017 (10) SCALE 1.

2. Accessible online at: www.trai.gov.in/sites/default/files/Consultation_Paper%20_on_Privacy_Security_ownership_of_data_09082017.pdf

3. In the EU the applicable regulation is General Data Protection Regulations (“GDPR”); approved and adopted by European Parliament (“EU”) in April 2016 and will come into force on 25 May, 2018.

4. Section 2(1)(za) of the IT Act states: “originator” means a person who sends, generates, stores or transmits any electronic message or causes any electronic message to be sent, generated, stored or transmitted to any other person but does not include an intermediary.

5. Section 2(1)(w) of the IT Act states: “intermediary” with respect to any particular electronic message means any person who on behalf of another person receives, stores or transmits that message or provides any service with respect to that message.

6. A regulator proposed to be formed under the data protection laws for enforcement (discussed later).

7. Black’s Law Dictionary 2004 (8th Edition) defines comity as “A practice among political entities (as nations, states, or courts of different jurisdictions), involving esp. mutual recognition of legislative, executive, and judicial acts. “‘Comity,’ in the legal sense, is neither a matter of absolute obligation, on the one hand, nor of mere courtesy and good will, upon the other. But it is the recognition which one nation allows within its territory to the legislative, executive, or judicial acts of another nation, having due regard both to international duty and convenience, and to the rights of its own citizens, or of other persons who are under the protection of its laws.” Hilton v. Guyot, 159 U.S. 113, 163–64, 16 S.Ct. 139, 143 (1895).

Welcome Legally India's Spring 2018 Issue

If you would like to receive future editions, please click here to register your interest.

Our Spring 2018 print and digital edition of Legally India, a joint publication by Global Legal Media and Legally India, has a strong disputes flavour, and examines: AI, global litigation risk, GC wishlists and more than a dozen jurisdictions and practice areas.