The link between investment and speedy and effective dispute resolution

No country can attract foreign trade and investment without a modicum of rule of law and stability in governance. Rule of law requires not only a set of easily understood norms and procedures, but also independent institutions where such norms are enforced without fear or favour. It is no coincidence that Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice features a trial scene: Venice’s wealth as a trading nation was built on its institutions’ ability to impartially and rigorously enforce contracts in accordance with the law. Hubs of commerce in the modern world such as London, Singapore, Hong Kong and Dubai all boast of excellent institutions designed to resolve commercial disputes in an impartial, effective, and efficient manner.

Efficient and effective resolution of disputes reduces transaction costs and the friction of doing business. Impartiality ensures that precedents are created in a stable manner, and all parties have faith in the system’s working. The link between investment and economic growth, and the rule of law has been well established in multiple studies across the world. As India looks to take sustainable economic growth to the next level, inviting greater levels of investment and engaging in international trade and commerce, the strength of its institutions and constitutional governance will be put to test.

The problems with commercial litigation in India

Unfortunately, over the last few decades, India’s institutions have not been able to respond to the challenges of a growing Indian economy and the fundamental changes taking place. The present judicial system is a descendant of the courts set up under colonial rule. While they were independent in their own way1, they followed (then) modern rules of procedure and evidence that made them attractive to litigants. These courts were still too few given the size of the economy and perhaps the vast bulk of disputes were still resolved informally and outside these formal judicial institutions.

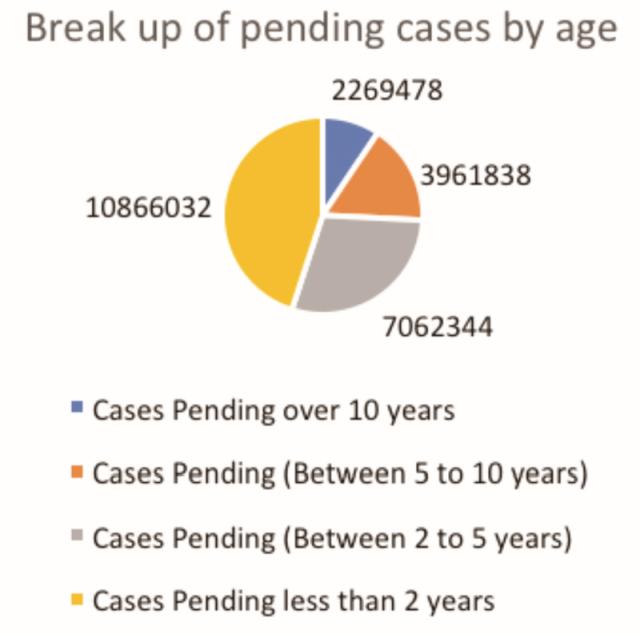

Today, the Indian judicial system is a gargantuan beast; as per latest figures available, there are more than 17,200 judges in India at all three tiers of the judiciary,2 more than 20 million cases, civil and criminal, are instituted in a year,3 and some 32 million cases are pending as of 2016.4 These figures though don’t tell us too much about how the system itself is working and the problems become apparent once we start examining them in some depth.

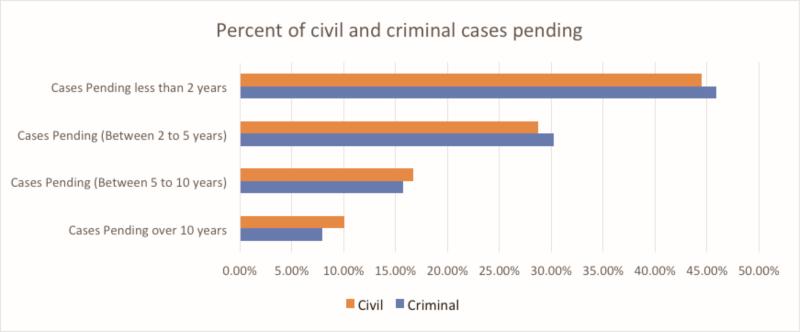

A chronic problem of the Indian judicial system is that of delay. The latest figures on the government’s “National Judicial Data Grid”, recently set up for statistical access online, suggest that 55% of cases have been pending for more than 2 years in the trial courts. Of the cases pending for more than two years, nearly half or 25% of all cases pending, have been in the system for more than five years, and a shocking 9% of all cases have been pending for more than ten years. Though there is no official time frame prescribed for the completion of a case in any law, a general rule of thumb that has been adopted in the last few years is that a case would be delayed if it takes more than two years to be disposed of. By that metric, 55% of the pending cases in India are already delayed.

The delay can be attributed to a variety of causes; the 266th Report of the Law Commission of India presented some shocking data on the number of working days in trial courts, lost to strikes by lawyers India. In some districts, no work took place in almost half the scheduled days in a five-year period in the district as lawyers struck work for one reason or the other, some utterly bizarre. Snap strikes called by lawyers is clearly one reason why the courts have been unable to dispose of cases quickly enough.5

The absence of sufficient numbers of judges is another possible cause. Across high courts, as per the latest data, 482 out of 1,079 positions of judges are unfilled. The situation is slightly better in the trial courts – as of September 2016, 4,846 of 21,374 positions were unfilled.6 Even without dramatic improvements in efficiency, filling the posts and having them work at the same disposal rate as other judges could see a dramatic improvement in disposal rates. Of course, in some high courts, the number of pending cases is so large, and the efficiency is so low, that it may not be possible to realistically address the issue by adding more judges.

Another possible cause for delays was recently unearthed in a study by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Examining the data related to cases filed in the Delhi High Court in the years 2011-2015, Vidhi found that adjournments were sought by the lawyers was a leading cause for delay – occurring in over 90% of delayed cases.7 This is not to suggest that this is exclusively the fault of the lawyers – rather the system, the judges, the lawyers, and the rules allow for this kind of laxity to persist and pervade making speedy and effective disposal of cases that much more difficult.

The Law Commission’s involvement

Even though some of the specifics of the problems of commercial litigation in India have only come to light recently, the general contour of the problems have been known for a while. It was for this reason that the Law Commission addressed the problem of commercial litigation in its 188th Report in 2003 recommending the creation of “commercial divisions” in high courts across the country. This was followed by a Bill presented in Parliament in 2009. However, there were flaws in the way the Bill was drafted and when pointed out, the Government of the day withdrew it and referred it back to the Law Commission to address the flaws pointed out in Parliament.

This ultimately resulted in the 253rd Report of the Law Commission of India on Commercial Division and Commercial Appellate Division of High Courts and Commercial Courts Bill, 2015. The Law Commission re-drafted the Bill, making it clearer while expanding the scope of changes to procedural laws to make disposal of commercial cases quicker. The Law Commission drew upon the experience of the United Kingdom, following the reforms suggested by Lord Woolf in the Access to Justice Report, 1996 and also the rules of procedure laid down by the High Court of Singapore. Both these countries being hubs of commercial litigation, not just for their own residents and businesses, but from those around the world.

The Law Commission also drew on extensive data to try and pinpoint the exact source of the problem with commercial litigation in India. Examining the pendency of civil suits in the high courts with original jurisdiction, the Law Commission found that 75% of civil suits had been pending for more than two years and thus delayed. The data contained in the Law Commission report is presented below:

The most significant change recommended by the Law Commission relates to the way in which the judge has now been empowered under the procedural laws to take charge of the litigation and ensure that it is brought to a swift and logical conclusion. This gives less leeway for parties to use the litigation process as the punishment itself and avoids needlessly prolonging the matter.

A clean slate: The Commercial Courts Act

The Government of the day has adopted the recommendations of the Law Commission and eventually, the Commercial Division and Commercial Appellate Division of High Courts and the Commercial Courts Act, 2016 was passed by the Parliament. The key features of the law are as follows:

a. High courts with the jurisdiction to hear suits, namely the Bombay, Calcutta, Delhi, Himachal and Madras high courts will be empowered to set up “Commercial Division” benches in the high court to exclusively hear commercial cases where the amount at stake is more than one crore Rupees (approximately GBP 120,000 or USD 155,000)

b. In other areas where a district court is empowered to hear civil suits, “commercial courts” can be set up by the Chief Justice of the high court in consultation with the State Government.

c. Wherever a commercial division or a commercial court is set up, a “commercial appellate division” – a two judge bench – will be constituted in the high court to hear appeals from the orders of commercial divisions and commercial courts.

d. Commercial divisions and commercial courts will exclusively hear only commercial cases assigned to them.

e. Commercial divisions and commercial courts will follow the rules of civil procedure as modified under the Commercial Courts Act.

Keeping in mind the need to reduce delays in the proceedings, the Commercial Courts Act amends the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 in so far as it applies to commercial cases. Some of the important changes are:

a. Mandatory award of costs to the successful party in a litigation.

b. Easier procedure to obtain summary judgment in a summary suit.

c. Case management hearing to ensure that proper timelines are fixed for completion of trial d. Detailed rules for discovery for discovery of documents e. Improved procedure for producing and leading evidence What’s happened so far? The Delhi and Bombay HC experience It is only last year that Commercial Divisions have been set up in the Bombay High Court and the Delhi High Court, and a year is too little time to properly assess the functioning of the commercial divisions. Nonetheless, there are some encouraging trends which merit comment.

Courts are taking the time limits laid down in the act seriously. The Delhi High Court in Saurabh Agrotech v Radhey Shyam Agencies8 has made it clear that there is no discretion vested in the court to extend time in cases where the parties have failed to file documents in time.

Courts are also being strict about the imposition of costs. Unlike the CPC, the Commercial Courts Act makes the impositions of costs mandatory in each case, and failure to do so has to be explained by the judges. This principle has been rigorously followed by the courts which are implementing it so far.9

Likewise, the limitation on the number of appeals and when they may be applied has also be interpreted in accordance with the spirit and the goals of the Commercial Courts Act.10

While a detailed assessment of the efficacy of this law is still waited, there is no reason why it can’t be extended, on a trial basis to other cities in India as well. While Mumbai and Delhi account for much of the commercial litigation in India, Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Chennai, Hyderabad and Kolkata also account for a fairly large number of commercial cases in the country. These cities being the hubs of investment and economic activity.

Should the commercial courts prove successful in the reduction in time taken to dispose of complex commercial cases in India’s courts, there is no reason why the procedural rules cannot be adopted for the disposal of all civil cases, irrespective of value or subject matter.

NOTES

1 See Abhinav Chandrachud, “An Independent, Colonial Judiciary”, Oxford 2015, Oxford University Press.

2 According to figures available on the national judicial data grid and the Department of Justice as of 29 April 2017.

3 Alok Prasanna Kumar, “Are people losing faith in the courts?”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 52, Issue No. 16, 22 Apr, 2017.

4 Supreme Court of India, “Court News”, Vol XI Issue No 3, available at Law Commission of India, “The Advocates Act, 1961 (Regulation of Legal Profession)”, Report No. 266 March 2017, available at Court News, n 4.

7 Nitika Khaitan, Shalini Seetharam, Sumathi Chandrashekharan, “Inefficiency and Judicial Delay”, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, March 2017 available here: 2016 SCC OnLine Del 6134.

9 See for instance Dashrath B Rathod v Fox Star Studios India Pvt Ltd 2017 SCC OnLine Bom 345.

10 See Sushila Singhania v Bharat Hari Singhania 2017 SCC OnLine Bom 360.

This article is brought to you by India Unleashed

India Unleashed is a print and online publication by Global Legal Media and Legally India, providing country-by-country insights and sector-specific analysis from leading law firms and writers around the world.