0. Synopsis

This article makes a case that appropriate process for appointments of Judges of higher courts requires development and publication of ‘metrics’ heretofore not available to the People.

It is pointed out that an ‘eminent person’ of the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) is necessarily a person armed with the knowledge that is only possible with such ‘metrics’.

The Constitutional right to information of the People is explained to charge even the Judiciary with the affirmative duty to maintain and expose in appropriate electronic format, various records that serve public interest.

As a basis in asserting such a broader duty, the new technological capabilities provided by the Internet age are articulated, and it is consequently argued that the Constitutional rights of the People are broader than those under the existing legislation of Right to Information Act, 2005.

A case study is then presented with respect to the ‘operational flows’ at the High Court of Karnataka at Bangalore, to show that important metrics can be generated without substantial additional overheads and also without potentially implicating questions of security, privacy or any legitimate state interests.

It is finally urged that the computer systems being employed by various organs of Government ought to be viewed as national resources that ought to be designed/developed not just as tools for administration, but also considering the government obligations under Constitutional Right to Information of the People.

Content Index

I. Constitutional Structure – Accountability of Judiciary to the People

II. Judicial Appointments – Some Background

III. Metrics Related to Judiciary – Some Background

IV. Case Study – Operational Data at the High Court of Karnataka

V. Sample Metrics for Appointments and Transfers

VI. The People, Process and Technological Infrastructure Required

VII. Evolution of Communication Capabilities & Divergence of ‘Information’ from ‘Data’

VIII. Providing Records – Right to Information Act, 2005 (“RTI Act”)

IX. Constitutional Right to Information – Broader Duties of the Government in the Internet Age

X. Thoughts and Next Steps

I. Constitutional Structure – Accountability of Judiciary to the People

It is often said that the people are the masters and the three branches of the government (i.e., Judiciary, Executive and Parliament) are merely agents of the people. In other words, the three branches are deemed to be subservient to the people, while being required to operate in the best interests of the people.

Examined from that perspective, Judiciary can be viewed as a ‘service organization’ serving the people. The substantial powers vested by virtue of the Constitution does not change that character of the relationship of the Judiciary as against the people. In fact, the magnitude and seriousness of the duties are only enhanced as a result. It is therefore reasonable for the Judiciary to be accountable to the people directly, in some important core respects, at least when such accountability does not interfere with the discharge of their constitutional functions.

Fundamental to the efficacy of any service organization is how consistently best suited persons are appointed to important roles and how various aspects of the operation are measured, as a basis for steering the organization (here Courts), even if such steering is performed exclusively by the Judiciary.

The Constitutional positions of Judges at High Courts and Supreme Courts undoubtedly qualify as such important roles, when the judiciary is accepted as a service organization. Properly designed and measured metrics provide extremely relevant information on suitability of a person for appointment, in addition to insight into any operational inefficiencies or improper biases (based on factors such as region, sex, caste, religion, etc.), that ought to be avoided in the discharge of the judicial duties.

The sections below examine how greater accountability can be brought directly to the people in the appointment of judges and the operation of the courts.

II. Judicial Appointments – Some Background

Over the period of 1981-1998, in the course of the cases referred to as ‘Three Judges Cases’, the court evolved the principle of judicial independence to mean that no other branch of the state - including the legislature and the executive - would have any say in the appointment of judges. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Judges_Cases

Under the recently (2014) passed amendment to the Constitution of India, the power to make recommendation for appointment will instead be vested with National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) comprising Chief Justice of India (Chairperson, ex officio), Two other senior judges of the Supreme Court next to the Chief Justice of India - ex officio, The Union Minister of Law and Justice - ex-officio, Two eminent persons (to be nominated by a committee consisting of the Chief Justice of India, Prime Minister of India and the Leader of opposition in the Lok Sabha or where there is no such Leader of Opposition, then, the Leader of single largest Opposition Party in Lok Sabha), provided that of the two eminent persons, one person would be from the Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes or OBC or minority communities or a woman.

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Judicial_Appointments_Commission).

While the system seeks to arrive at the appropriate balance of power between the three branches of the state in the appointment and transfer of Judges, the necessary information that ought to be available (as one of many variables to be considered) to each decision maker, as well as the people, ought to be carefully considered.

Metrics easily determinable based on normal course of operation of the courts are submitted to be such essential information, both for the decision makers and the people as well.

The NJAC Amendment to the Constitution is under challenge at the Supreme Court for vires and on other legal grounds. The Bench adjudicating the case is reported to have asked Attorney General Mukul Rohatgi, “Our experience tells us about people (being considered for appointments). Whether it is possible for you to suggest two names, who will be able to suggest the names of the judges? The question is whether you can name a person of eminence who can name judges,” the Bench asked.

While there are not many persons of eminence who can name judges, as the Honorable Bench rightly points out, there are unquestionably many eminent persons who, when armed with proper metrics and other information, will be able to ensure with more certainty and consistency, the appointees (as Judges) are within a range of reasonable meritorious alternatives. Such eminent persons can be those that have excelled in their respective fields (including mere public service, industry, education, etc.), and have a demonstrated record of constructive engagement with peers of equal or more power/control in a broad range of issues in their core job or outside. Several luminaries qualify as eminent persons under this definition, if their purpose is to aid in channeling the selection process. Metrics will certainly help such luminaries in addition to bringing Judicial accountability directly to the people.

Having asserted the relative importance of ‘metrics’, we now examine some background on metrics and the related technical/legal aspects.

III. Metrics Related to Judiciary – Some Background

In an opinion published By Sh. Prashant Reddy, a Delhi based Advocate, on 16 June 2014, entitled, “To fix the most fundamental problems of the Indian judiciary, we must finish what Fali & others started” at https://www.legallyindia.com/, it was stated:

In 2004 eminent lawyer and Senior Advocate Mr. Fali S. Nariman who was then a MP in the Rajya Sabha introduced in Parliament the Judicial Statistics Bill, 2004. This proposed legislation was aimed at creating authorities at the national and state level to collect, in a scientific manner, statistics from each and every courtroom regarding the hours taken by the Court to hear the dispute, the time between the filing of the case and hearing by the court, the adjournments granted, time taken for delivery of judgment after it has been reserved, along with the names of the lawyers and judges responsible for the case. Imagine the possibilities if all this data was made available on a computerized database. Not only would it provide information on the efficacy of the judges but also help litigants separate the litigating lawyers from the adjournment lawyers.” (http://bit.ly/1Hje2TG)

The statistics sought to be gathered by the above noted Bill would undoubtedly have served as the basis for generating actionable metrics. However, a systematic effort along the lines of the Bill does not seem to have been undertaken.

However, as explained below, careful consideration of the technological advances and the processes recently employed by the Courts shows that the objectives sought to be achieved by Sh. Nariman’s bill and advocated by Sh. Reddy, can/should be achieved merely by proper electronic ‘book-keeping’ associated with the daily operation by the Courts (as done currently), and deployment of fairly well-understood technologies to open the data to the public electronically in suitable formats.

The challenges with the absence of the data in suitable formats is brought out in an article entitled, “Ctrl+C and other stories” at http://blog.dakshindia.org/2015_01_01_archive.html. As clear from there, Daksh is a Bangalore based NGO seeking to perform research under “The Rule of Law Project” and set out to collate some publicly available records from Courts’ operational processes, in a form suitable for processing by computers. There were several documents published by Courts from different states in PDF files or merely as display on computer screens. Even for the miniscule amount of data (compared to the vast amounts that can provide material actionable insights) they sought to compile from such sources, they had to spend substantial effort and eventually develop complex software utilities to get the data in a suitable format.

Comparison with US in this respect is quite apt, and it is stated at the below URL that many such records would have been provided by the Governments agencies in electronic format that is amenable for further processing by programs such as spread sheets.

https://ogis.archives.gov/for-foia-requesters/Database-Requests-Best-Practices-for-Requesters.htm

Such a facility consistently across Courts of all states would have facilitated Daksh or similar organizations having interest in data analysis, to easily procure the relevant data.

It is now shown that the character of the base data sought by Sh. Nariman, Daksh and Sh. Reddy is in many cases public and already captured by computers, but the computers may not have been merely designed carefully to provide the facility of further analysis.

IV. Case Study – Operational Data at the High Court of Karnataka

There are clearly multiples components of data that are exposed to the public at the High Court in Bangalore, which would be of interest from metrics viewpoint.

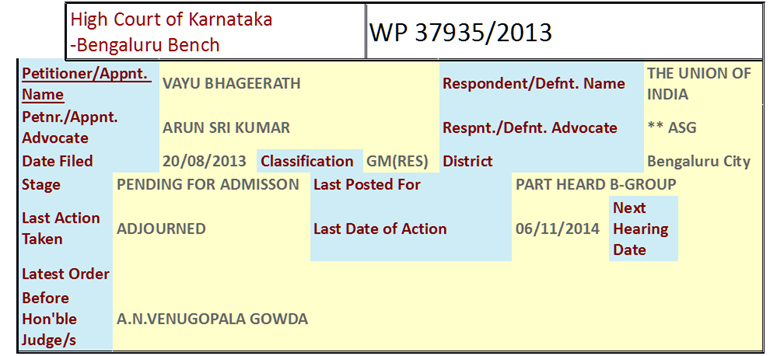

Figure 1 below depicts the status of each case that is made available on the Web at http://karnatakajudiciary.kar.nic.in/caseStatus_CaseNumber.aspx. This constitutes the first component.

Figure 2 depicts the Causelist data (constituting the second component noted above) published for each Judge/Court hall (at http://karnatakajudiciary.kar.nic.in/dailyCauseList_Judge.asp) on a given day, and indicates the list of cases that Judge will possibly hear that day and the sequence in which those cases will be heard:

Given that any Advocate may have to attend to proceedings in multiple court halls (before corresponding Judges), in the normal hours of the Court (10AM-7PM), the specific item number (one of 7-10 in Figure 2) currently being heard by the Judge is displayed. This helps an Advocate to know the status in any court hall from anywhere in the building premises, and timely attend the cases in different court halls s/he is responsible for on that day.

This means the start time and end time in hearing each case are necessarily established by the corresponding operation, and this constitutes the third component of the data. It is unclear whether the displayed information is recorded as corresponding data items, but it is a fairly trivial technological exercise to record these times, integrated with the process being followed at the High Court, should it be decided to move forward in that direction. Irrespective, the absence of the data records for further processing does not change the general conclusions reached by this paper.

The Honorable High Court of Karnataka also maintains a list of classification codes published at: http://karnatakajudiciary.kar.nic.in/noticeBoard/casetypes.pdf, and the corresponding code is shown in Figure 1 associated with the specific case as well.

In addition, the Honorable High Court publishes the composition of each bench and the specific classes of cases the Judge(s) on the corresponding bench would hear in each duration.

Lastly, the High Court website has a brief profile of the Judges, including date of birth, year in which confirmed as High Court Judge and general areas of expertise if/when practicing as an Advocate.

A skilled analyst/programmer will readily confirm that the data of above, if accessible in proper electronic format, is sufficient for fairly compelling metrics on individual Judges and Courts, some of which is explained below.

V. Sample Metrics for Appointments and Transfers

With respect to ‘Appointments’ we consider two scenarios – (1) an Advocate at the High Court being elevated as a High Court Judge; and (2) A High Court Judge being considered for elevation to Supreme Court.

As to (1), from the data described above, assuming it is available for processing by a computer program, it is a fairly simple exercise for a programmer to generate the below metrics for all advocates, including those seeking to be appointed as a High Court Judge.

- The number and mix of cases the Advocate has handled by different classifications (a good candidate necessarily handles a breadth of cases and also a large number of cases)

- How frequently does the Advocate ensure disposal of cases (a good candidate demonstrates ability to close cases by bringing clarity to the issues, instead of seeking continuous adjournments)

- How much Court Time (hearing time) does the Advocate take/get, as measured against individual Judges, Case Types, etc. (a good candidate, with appropriate clarity and submissions, should be able to get cases resolved with minimal court time and also shorter time line).

- Does the Advocate seek justice from a broad array of Judges or engages in excessive forum shopping with individual judge(s)? (A good candidate necessarily shows the record of having approached different Judges)

- Count of appeals and favorable disposition (a sound lawyer is likely to have appealed less, and is more likely to have favorable dispositions).

It is unclear if the systems of the Courts track the details such as how promptly the Advocate files appropriate responses, when required by the applicable procedure. The information noted above does not speak to that point. If the information is tracked by the court systems, it will be quite relevant to understanding the suitability of a candidate as a High Court Judge, since a good candidate shows a record of respecting the legally set deadlines for filing responses.

As these numbers would span a period of many years of practice for an Advocate, it could give a one relevant indication of suitability or unsuitability (of a candidate) for elevation to the bench. In a sound consideration procedure, both suitability and unsuitability, must be examined as separate aspects before the eventual decision on whether or not to appoint an Advocate as a High Court Judge.

From the perspective of People, the metrics at a broader level (not just those of the candidates being considered for appointments) are important since the comparisons facilitated operate to provide more meaningful benchmarks for evaluation of merit, especially by the ‘eminent persons’ of NJAC proposed to be at the core of the appointments process.

As to (2) now, a programmer will easily be able to generate below metrics for a High Court Judge, seeking elevation as a Supreme Court Judge:

1. The number and mix of cases disposed of by the Judge, with the mix measured in terms of subject matter, year of filing, and year of disposal, etc. (a good Judge has command over a broad areas of law, and has a good disposal rate of short and long term cases)

2. The breadth of Advocates approaching the Judge for justice/decisions (a good Judge necessarily attracts a breadth of Advocates for decisions)

3. The number of times appeals are preferred for Judge’s decisions, and favorable disposition or reversal, on appeals of the cases decided by the Judge at various levels.

The metrics of above are merely representative, and one can analyze different combinations or subsets of various facts. For example, metrics can be examined for biases, whether unintentional or intentional. As an illustration, metrics can be easily generated to see if a specific group of lawyers (based on region, sex, religion, caste, language, etc.) receive more/less favorable treatment compared to another group across different Courts/states/Judges/years.

For the totally uninitiated in computing technologies, a good starting point is to understand ‘pivot tables’ and filters, in Spreadsheet technologies such as Microsoft’s Excel Software to recognize the broad types of metrics that can be generated, once the data is available for processing by computers in a suitable format.

It is worth mentioning that Karnataka High Court has the practice of appointing a third of the High Court Judges from lower courts (e.g., District Judges, etc.). It may be appreciated that metrics there offer a more precise indicia of merit since the pool of Judges are arguably performing a similar function for several years in their careers. Disposal rates, breadth of cases disposed, record on appeals, etc., are clear numerical indicators of merit in elevation of such Judges to Higher Courts. Quality is a more subjective aspect, but objectivity can be brought by appropriate evaluation processes.

Assuming one is convinced of the relevance of metrics, it is now established that the additional technological and people overhead for the Judiciary is not substantial, considering the state of the technology.

VI. The People, Process and Technological Infrastructure Required

It is assumed that Courts already have the computing and people infra-structure to maintain the data records in accordance with the Figures pointed above (as the High Courts in Karnataka appear to). This paper does not advocate (or discourage) Courts to process the data records further and publish meaningful metrics. Rather what is urged is to merely ‘expose’ the data records in a form that lends to processing by computers of external parties.

Here is what would be specifically required to be done with such an approach. First, the data records would need to be stored according to appropriate database technologies. Normally, this would mean that the data is stored as a few tables in a database system, with each event (e.g., hearing, paper submission, filing, etc.) being ‘added’ as a record. This would be part of basic record-keeping, which is likely already being performed, since it is the most logical way software analysts design software systems.

Providing the capability to download any data records of interest into Spreadsheets will be useful in many instances, and that would require some extensions to the software infrastructure.

However, as numerous records get added on a daily basis in different Courts of the country, one may consider deploying a web server as a front-end to the database system, and is probably the only additional hardware component required. The web-server would respond to queries about data added as records. The data records are quite structured, and would be amenable to further processing by the external computer systems. NGOs, colleges, foundations, etc., are likely to deploy such computer systems and provide valuable analysis to the public. It is likely some of them will provide user interfaces for public to query their software systems for meaningful metrics or other organized data.

Now addressing the possible overheads, for purpose of metrics for judicial appointments, some level of errors (say within 2%) would not change the character of answers provided, and therefore process-wise it is believed there will not be much additional burden on the judiciary from a process perspective.

From people requirements perspective also, the burden is not substantial. Irrespective, these record management functions, which are not tightly coupled to service delivery or production, can be conveniently performed from mid-town/rural areas, with any outsourcing if required. The Government should seriously consider this alternative, as it provides a meaningful opportunity to create jobs in the less crowded areas, while offering compelling benefits to the broader People being served.

From machines/technology requirements perspective, again it is not a substantial effort and several service providers will be able to provide the necessary technological infrastructure at quite affordable prices, since this is a rudimentary technology, considering the general complexities addressed in the industry.

It is therefore concluded that the overheads in terms of people requirements, process, and technological support requirements, is not a reason to defer the development of appropriate infrastructure that lends to powerful insights in operation of the Courts.

It must be appreciated that the approach suggested herein provides multiple parties to perform the data analysis to provide diverse viewpoints, and it is thus a superior approach compared to any single party (including the Judiciary alone) providing analysis/metrics.

In terms of understanding the legal and constitutional right of people over such capabilities, a critical aspect is appreciating how evolution of modern technologies is further distancing ‘information’ from ‘data’.

VII. Evolution of Communication Capabilities & Divergence of ‘Information’ from ‘Data’

Definition of some terminology is apt for consistent understanding and expression of the underlying concepts.

‘Data’ is merely representation of an underlying factual occurrence. When the data is recorded for reproducibility, it is termed as a ‘data record’. It is critical to understand when we treat the record as mere ‘data’ versus ‘information’. There is a critical difference between the two, as explained on one representative web source:

Data is raw, unorganized facts that need to be processed. Data can be something simple and seemingly random and useless until it is organized. When data is processed, organized, structured or presented in a given context so as to make it useful, it is called information.

Data" comes from a singular Latin word, datum, which originally meant "something given." Its early usage dates back to the 1600s. Over time "data" has become the plural of datum. "Information" is an older word that dates back to the 1300s and has Old French and Middle English origins. It has always referred to "the act of informing," usually in regard to education, instruction, or other knowledge communication.

http://www.diffen.com/difference/Data_vs_Information (Emphasis Added)

The key difference between data and information is that data is mere reflective of a fact, but data is transformed to information as the corresponding effect is to ‘inform’ the target audience. Using ‘data’ and ‘information’ interchangeably is merely being blind to what the words mean in their essence, as well as technological advances in computing and communication that have pervaded our lives in the past few decades, as further explained below.

The evolution of the communication capabilities historically can be seen as operating to ‘inform’ the target people more. Thus, the magnitude of opportunity to be informed has increased vastly as the communication medium has evolved from spoken word (language), to written word (script), to copying (print/paper), to electronic (computing and communications).

The recent electronic medium differs from the earlier print/paper medium in three substantial respects: (A) ubiquitous access; (B) ‘computational capabilities’; and (C)‘dynamic data organization’ capabilities. These aspects, particularly in combination, operate to ‘inform’ one, at an enhanced scale unimaginable when compared with that possible via the print medium. Each aspect is briefly and broadly established below for purpose of completeness.

As to (A), ubiquitous access has been established with the operation of ‘Internet’ in its most primitive form. The provided web pages/services can be accessed at a time that is convenient for the seeker, with fairly negligible marginal additional cost of medium if the Internet and computers are assumed to exist for the seeker already.

As to (B), computational capabilities have been integrated into the presentation of accessed pages for the first time. In print medium, the record keeper may need to perform such computations and the seeker is generally limited by what the record keeper chooses to provide. In sharp contrast, the recent electronic medium provides a general infra-structure by which the seeker can choose the various views/computations of interest, many times with the ability to specify complex computations matching her/his enquiry of interest, which are simply received as a part of the web page accessed.

As to (C), there are two dimensions – ability to examine the same data (potentially many thousands of events) with different views, and also integrate data from different sources into a single view.

As to the combination of B and C above, an illustrative example is helpful in this context. Assuming each High Court continues with its own operation and record keeping elelctronically, akin to the Karnataka High Courts as explained above, each of many analytics organizations (schools, NGOs, foundations, etc.) will be able to provide a single table view of number of cases being disposed of by each state of the Union of India, broken by years, classifications, Judges, etc. The data is seamless integrated and analyzed electronically, in ways unimaginable only based on the print medium.

A filter can be easily employed to limit the view to particular case types of interest (e.g., cases decided in Constitutional Law only, or by Judges who are older than 55 years or Judges serving out of state). The views can provide averages type any statistical information related to any of the columns of the table. Each view can be specific to what the seeker wishes to view, and the seeker can specify fairly complex models for viewing.

Clearly such capability is generally not possible with paper/print medium, and information clearly diverges substantially from data with the evolution of the electronic medium. The relevance of this observation will be clear when examining the section on Constitutional Right to Information below.

We now examine the legal theories under which people may obtain such capabilities to examine the performance/operation of various courts. First we look at the Right to Information Act 2005, and then broadly from a Constitutional Perspective.

For the purpose of next section alone, it is assumed that the data records related to various operations, as noted above with respect to Karnataka High Court, will be made available as for further processing by computers.

VIII. Providing Records – Right to Information Act, 2005 (“RTI Act”)

Section 2(i) of the RTI Act defines a record to include “…(d) any other material produced by a computer or any other device;”. Thus, the data records discussed above (which are already generated or maintained by the Courts) are clearly covered by the definition of records under RTI Act.

Section 2(j) of the RTI Act defines the right under “right to information” as including, “…(iv) obtaining information in the form of diskettes, floppies, tapes, video cassettes or in any other electronic mode or through printouts where such information is stored in a computer or in any other device;” (Emphasis Added).

The serving of up-to-date structured data lending to analysis via web servers is clearly covered by the highlighted text, in particular the ‘electronic mode’. In other words, the Courts would be required to support computer-to-computer communications so that third parties can retrieve the records regularly and analyze the data.

This approach is consonant with the express statement in the RTI Act that, “Every public authority should provide as much information to the public through various means of communications so that the public has minimum need to use the Act to obtain information.” Therefore, the RTI act encourages proactive disclosure of information consonant with the approach urged here.

Therefore, the RTI Act itself arguably mandates that the Courts expose (make available for retrieval according to computer-to-computer protocols) the data records via well-defined computer to computer interfaces.

In the article by Sh. Reddy referred to above, there is a section entitled “The Judiciary’s battle against the RTI”, with references to a few cases where the Courts have resisted application of RTI Act to the Court’s activities. Many of those cases are clearly inapplicable in the present context since the scope of data records sought here are already in public domain individually. What is requested is merely to expose that data already maintained, according to proper computer-to-computer interfaces (or other suitable formats) for further processing as ‘information’.

Now we move onto the duties with respect to records not currently maintained by the Courts.

The article of Sh. Reddy also notes a case filed by a RTI activist Commodore Batra with the Supreme Court, requesting the number of cases reserved by its judges for judgment between 2007-2009. The Supreme Court Registry is reported to have initially refused to provide such information on the grounds that it did not maintain such records, while on further appeals the issue was resolved in favor of Commodore Batra. Wikipedia clarifies the term reserving decision/judgment as, “After the hearing of a trial or the argument of a motion a judge might not immediately deliver a decision, but instead take time to review evidence and the law and deliver a decision at a later time, usually in a written form.”

It should therefore be assumed that the information systems supporting the operation of the Supreme Court do not have a database system, which logs one computer record when a Judge ‘reserves his decision’, and another computer record when the decision is actually delivered. In a properly designed database system having such records, generating and formatting the results is usually a matter of less than half an hour. Assuming the data records are exposed for (electronic) querying as proposed in this paper, the public can retrieve this information without having to approach the Court Registry. This is a benefit, in addition to considering the performance/bias record of the Judge for appointments/transfers noted above.

The scenario raises a fairly fundamental and very important question from the perspective of People – does the Court have the duty to maintain electronic records in relation to ‘reserving’ the Judgment and when the decision was eventually rendered. A plain reading of the RTI Act suggests that the duty there is to only share the records maintained as respect to day-to-day transactions, but there is no duty to actually create/ maintain such records. It appears the Supreme Court registry’s initial refusal to answer the query there was based on that understanding of the RTI Act.

The above fundamental question is now analyzed under the Constitutional Right to Information.

IX. Constitutional Right to Information – Broader Duties of the Government in the Internet Age

It has been time and again affirmed that the Right to Information is one of people as masters, and inherent in the Constitution. However, the understanding of the bundle of rights inherent to the Constitution continues to evolve in the past 1-2 decades. One would reasonably agree that the bundle of rights inherent to right to information is a function of the communication capabilities. More rights should be deemed to be added to the bundle as the communication capabilities evolved from spoken word (language), to written word (script), to copying (print/paper), to electronic (computing and communications). The rights are fundamentally in terms of ‘informing/understandability’ and ‘access’. As the communication capabilities evolved in that order, the people had progressively more rights in terms of being ‘informed’ and having access to the related information (as to the actions of the agents/rulers).

When examined from that perspective, it is abundantly clear that the RTI Act goes only as far as print medium and ‘mere arrival’ of the Internet as a new communication medium. The bundle of rights under the RTI Act is commensurate with print medium in that ‘copying’ of maintained records is confirmed as a right, which right would clearly be absent prior to the print/copying capabilities that evolved after the spoken word/language.

The RTI Act is also commensurate with ‘mere arrival’ of the Internet because initially Internet was used to provide ubiquitous access (any time, any place, at the finger tips of the information seeker) to ‘static’ pages only (i.e., content representing mere text that is pre-specified by the content provider). The requirements under the RTI act that information as to some roles and responsibilities be widely disseminated on the Internet, proactive disclosure of some general information, making records available via media such as disks when record are maintained electronically, etc., are only commensurate with the static aspects of the (new) electronic medium.

The new electronic medium has evolved to offer a lot more capabilities, in particular the ‘computational capabilities’ and ‘dynamic data organization’ capabilities, as explained in the section above. These capabilities, particularly in combination, operate to ‘inform’ one (the end result of constitutional right to information), at an enhanced scale unimaginable with the print medium.

It would be reasonable to assume there will be consensus among jurists at a general level that these capabilities add to the bundle of rights under the Constitutional Right to Information. Assuming that agreement is there, it would naturally follow that the people have the right to ‘metrics’ as well, since metrics operate to provide a much broader picture for the ‘masters/people’ in the operation of corresponding organ of the government, compared to the narrow view copy of any single record may offer under the RTI Act.

A good comparison point is The Freedom of Information Act, in United States of America. A section there states in relevant parts: (B) In making any record available to a person under this paragraph, an agency shall provide the record in any form or format requested by the person if the record is readily reproducible by the agency in that form or format. Each agency shall make reasonable efforts to maintain its records in forms or formats that are reproducible for purposes of this section. (5 U.S.C. § 552 As Amended By Public Law No. 110-175, 121 Stat. 2524). It does appear the Government Agencies in USA already have the duty to maintain and provide records in formats suitable for further processing. In other words, the data records are provided in a suitable format, which can be translated into metrics.

Now, we turn to the more complex question of whether the Judiciary would be required to add that field in relation to ‘reserving’ the Judgment, so that the records on ‘reserving judgements’ also can be exposed for further analysis, at least for the purpose of Judicial Appointments.

Obviously, an able Judge seeking elevation to the Supreme Court would be expected to have only reasonable time consistently between reserving a judgment and pronouncing the decision thereafter. Metrics in that respect are arguably within the purview of the Constitutional Right to Information, in view of the enhanced communication capabilities offered by the electronic medium.

Then, it is well established principle that the Judiciary is the final authority in pronouncing what the Constitution IS and it is arguably within their discretion to answer in affirmative or negative, whether the Registry is required to maintain electronic records as to ‘reserving the Judgements’.

It will be urged that the Judiciary concede this question in favor of the People so that a broad principle is established that the Constitutional Right to Information spans the duty to maintain reasonable electronic records related to material facts, which are amenable to further analysis. The principle potentially spans several critical operations in various organs of the government, where people have compelling interest in ensuring transparency and fair play. As the protectors of the Constitution, the Judiciary must be in the forefront of providing transparent systems.

Also, the Judiciary will be urged to recognize that the computer/information systems are not merely support tools for operation of complex government organizations now, but a necessary national resource just like environment (which gets passed down to generations down) or roads (which is a necessary for efficiency on a daily basis), which have to be properly nurtured and developed for the benefit of the People.

By first embracing the development of proper metrics with respect to its own operation, including agreeing to provide electronic records related to ‘reserving Judgements’, the Judiciary will have the continued legal and moral authority to enforce the Constitutional principles over other organs of the Government.

In summary, it must be recognized as a Constitutional Right that the Government organs maintain and expose appropriate electronic records, which would be of interest to public. Under that recognition, the Supreme Court will be urged to agree to maintain and expose records related to ‘reserving judgements’.

Before closing, it is worth a mention that around July 2002, the author of this paper along with Prof. Shivashanker, Indian Institute of Sciences, had mailed a letter to the India Supreme Court asking the Honourable Court:

(P1) to ensure that all The State Governments in the Union of India actively and affirmatively povide “information” (defined in sections below) on spending related to physical infra-structure (e.g., roads, bridges, flyovers) using the world-wide web;

(P2) to decree that the information sought in (P1) above to be within the purview of the right(s) recognised under the right to information/know or other provisions of the Indian Constitution; and

(P3) to provide guidance on the extent to which The State Governments would be required to provide information on various governmental activities on the world-wide.

The Petitioners received no response from the Honorable Supreme Court, which is quite understandable. However, in comparison to what was asked then, what is being asked is substantially simpler in the following ways:

- We are simply asking practical and easy extensions to what is being already performed by the Honorable Courts

- All the data records are individually already in public domain, and we are simply asking the Honorable Courts to expose those records in a way that lends to electronic processing

- The remedy sought is arguably within the control of the Judiciary (and no policing of external organizations is necessary).

Given that various organs of Government have embraced information systems to support their operations (just like Courts have), it is in clear public interest that a principle be established that these records are available for further analysis, and be followed by all organs of government where appropriate.

X. Thoughts and Next Steps

It is not author’s contention that metrics is a dispositive factor in determining the suitability of a person for appointment as High/Supreme Court Judge. Rather, it is simply that it provides one important dimension that external persons (such as Eminent persons of NJAC) will be able to use to ensure that the appointments happen based only on appropriate variables.

In the absence of such checks and balances, people have every reason to be concerned that any composition of appointment authorities will eventually degenerate into groups, with each group compromising with other group’s choices, to ensure its own choice is accepted in some instances at least. People would want to ensure every appointment is on its own merit instead, or at least metrics be used to identify most suitable candidates within such groups, if there is a legal sanction to such grouping.

Given that the information systems are established to be a national treasure (which ought to be developed and passed to subsequent generations), the Government should be urged to permit (if needed by appropriate legislation) private participation in auditing the design and implementation of information systems. For example, most competent analysts with understanding of the public requirements for information, would have designed the Court information systems (explained above) to be supported by appropriate schema/tables so that the metrics/analysis proposed here, would be done with simple efforts. Now, one cannot be sure of that aspect, though the paper assumes the table/ schema design preserves the data records of interest, for the required analysis. This issue would be there for potentially information systems being used by other organs of the government as well.

The Judiciary may establish a committee of experts (including ones with knowledge of law, and those that represent public interest for information) to clearly establish the fields/records that are to be maintained and exposed, associated with the Court’s information systems, considering the public interest as well as the interests of the administration/Registry, Advocates and Judges. The Committee shall take into consideration the applicable processes, laws and reasonable requirements of the public in formulating the Judiciary’s approach to Constitutional Right to Information.

The effort of the Judiciary may also include formulation of some uniform codes for classification of codes across High Courts, so that meaningful analysis can be performed across court of different states. It may be appreciated that uniform codes can be generated by the information systems, if they are proactively designed.

A similar effort can be undertaken for other areas of governance. Corruption and inefficiencies can be the guide in identifying such areas, in public interest.

The Government should consider establishment of support centres from smaller towns to support e-records management as off-line activities (i.e., not in the course of service delivery so that there is no disruption to the service delivery function). For example, each Advocate at High Court may be provided an account to view records as relevant to her/him, and work with the support centres to make any required corrections.

Finally, it is pointed out that ‘big data analysis’ is the currently evolving science which is touching many aspects of the sciences, education and industry. It would be unfortunate if the related expertise does not inure to the benefit of the public immediately, and the Honorable Courts are accordingly respectfully prayed to facilitate and embrace the development of metrics in public interest.

Naren Thappeta is a Bangalore based patent practitioner registered as an Advocate in India, as an Attorney with the bar of Washington DC, and as a patent agent with both India and US. He has a BTech degree in Computer Science from Andhra University (1985), and a JD/law degree from Santa Clara University, California.

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first

Thank you for taking the time to read the article and also for the comments. Just wish to add one thought, so that it is not lost on at least some.

While I have made a point in respect of 'judicial appointments/NJAC', my conviction is on a principle, which I have applied it now against Judicial appointments, and in 2002 against spending related to infra-structure. The nature of the transactions is different in the two cases, but the bottom-line is there is certain beneficial info that should be available to public and that leads to substantially better governance.

The changes sought are facilitated by the Internet and electronic medium, have broad ramifications in governance, and thus I am trying to read these rights into the Constitution.

Hopefully the article makes clear this point that Constitutional Right to Information is much broader than the copying facility provided by Right to Information Act, and the concerned authorities (Judiciary here, and other organs of government in other places) hopefully will align the laws/practices with the rights of People in view of the new Constitutional rights of the people in the Internet age.

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first