Despite all the legal firepower involved, it was far from certain that the case would go the way it did.

“We were wondering why no one has approached the Supreme Court and even thought of taking up the issue suo moto,” then Chief Justice of India (CJI) Altamas Kabir said after law student Shreya Singhal brought a writ petition to his court on 29 November 2012, asking for the Information Technology Act 2000’s Section 66A to be taken off the statute books.

But despite judges' obvious enthusiasm, it was only last week, on Tuesday 24 March 2015, that the Supreme Court struck down Section 66A, writing history with its most important pro-free-speach decision since 1960.

In those last two years, three months and 24 days, arrests under Section 66A kept coming, despite a January 2013 government advisory cautioning against indiscriminate arrests, while instances of intimidation of internet businesses and individuals continued. One of the petitioners, online reviews site Mouthshut.com, kept receiving legal notices, some fake signed by “senior advocate Ram Jethmalini” (sic) or fake purported Supreme Court orders made by long retired Supreme Court judges, according to Mouthshut.com lawyer Mishi Choudhary.

The case went on as other petitioners joined Singhal’s writ or filed parallel writs; Mukul Rohatgi, who had initially been briefed to argue in Singhal’s writ, became attorney general and Soli Sorabjee took over the case from him; Singhal, who had been preparing for her law admissions test when she first filed in 2012, went on to her first, then second year of LLB studies at Delhi University.

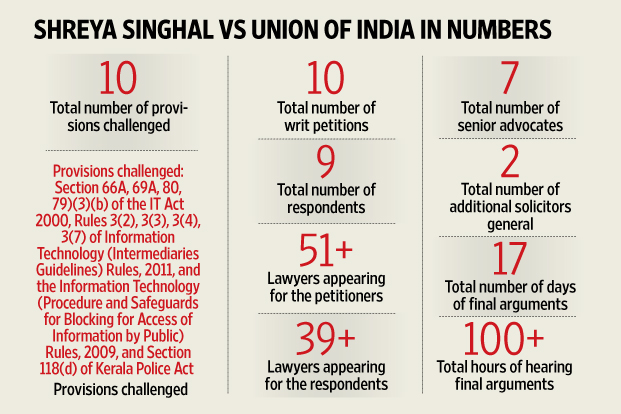

It also took two benches, three judges, 80 lawyers in the courtroom and several more behind desks drafting and researching (see box).

“But it is like that in the Supreme Court,” says Karuna Nundy who argued for the People's Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) NGO. Another lawyer for PUCL, Apar Gupta, stresses that when there are so many petitioners, it takes time.

Another counsel on the case, Gopal Sankaranaryanan, who argued for petitioner Anoop MK, notes that the case may have lost some of its urgency compared to “many other cases waiting in (the SC’s) wings for many years”, after the charges were dropped against two Palghar women who had been arrested in November 2012 under Section 66A for online criticism of the bandh following Bal Thackeray's death. “While it is very much a public interest issue, there are other important (pending cases) dealing with civil liberties,” he says.

That said, the subject matter of the case ensured it ignited the passion of thousands on Twitter and social media. Nundy notes that through the day-to-day hearing of this case the internet became a “very enjoyable (concept) to explore on a meta level”.

“I think the kind of process… thinking of new ideas and evolving jurisprudential arguments, some of them even during the process of the hearing, it was fun,” she says. “It is one of the reasons you become a lawyer, right?”

The case united a student, activists, core human rights crusaders, a politician, businesses and an artist who all aligned their interests in the courtroom.

Gupta remarks: “I’ve realized through working on this that incredibly well-meaning, intelligent people often disagree on small technicalities and nuances. And it is important for them to come together with respect to the common objective.”

That overlap in objectives was obvious even in court. Unusually, one arguing counsel, Mishi Choudhary, once stepped in during arguments to answer a query raised by the bench not to her client (Mouthshut.com) but to Gupta’s (PUCL). “The funny part was that there were 10 different petitions and no one was really going and working with each other but there was this beautiful coordination which we just saw because everyone’s principles were just the same,” she says.

Bench play

Despite all the legal firepower, it was far from certain that the case would go the way it did.

Justice Rohinton F Nariman wrote and, with his senior co-judge Justice Jasti Chelameswar, delivered the judgment on 26 March 2015.

One lawyer on Twitter called Nariman a “rockstar” for the judgment, but he was not initially party to that bit of history being made.

The substantive arguments for the petitioners had commenced before justices SA Bobde and Chelameswar in November 2014, starting with senior advocates Soli Sorabjee, KK Venugopal, Sajan Poovayya, and advocates Sanjay Parikh and Gopal Sankaranarayanan. Venugopal had argued for almost three days and Sankaranarayanan for two. Each day of hearing in the case lasted from 1030am to 4pm.

But after Sankaranarayan finished arguing in December 2014 the court broke for winter recess. After the recess its roster, as per the Supreme Court’s bi-annual routine, changed. From January 2015 onward Nariman became Chelameswar’s co-judge on one bench.

“Thankfully for us it was not a part-heard matter,” notes Gupta. If Chelameswar and Bobde had decided that the case was “part-heard”, only the same bench could have continued hearing the matter. This would have delayed the entire process considerably because under the new roster Bobde and Chelameswar were not sitting together in one courtroom anymore: a scheduling nightmare.

The bench rosters were set to change again in late February but in anticipation of this hurdle, Nariman and Chelameswar had given the government a limited number of days in which to finish its arguments. They also explicitly requested CJI HL Dattu to give them several extra days together to finish hearing the matter.

Both managed to wrap up the hearings in the nick of time on 26 February, sparing the matter more dilation before its conclusion. Nariman now sits with Justice AK Sikri, while Chelameswar sits on a bench with Justice RK Agrawal.

Any other way

Nariman may be the only Supreme Court judge to have his own YouTube channel (though he has not updated it since stepping up from the bar to the bench last year), but there is no obvious evidence of Bobde's tech-savvy. This influenced the dynamics and nature of questions the bench peppered advocates with. Choudhary swears that “every possible question was asked”.

Nundy recounts a statement by Bobde that given the varied audience and unique nature of the internet, netizens should simply be more polite online.

“Justice Bobde was reluctant to accept the argument on free speech under article 19 but he was willing to accept the article 14 (on why someone’s online speech should be protected less strongly than their offline speech),” says Sankaranarayanan.

Bobde’s focus seemed to be on understanding how the internet is a different speech medium and how it can have potentially harmful effects, notes Sarvjeet Singh, who attended all hearings in the matter in his capacity as project manager at NLU Delhi‘s Centre for Communication Governance.

“I don’t think had (Bobde continued hearing the case), the ruling would have (been different), especially because at Justice Bobde’s time the arguments were around 66A, so they were not on (website) blocking or the intermediary liability,” he says. “And the general stance, irrespective of the bench, was that 66A would have been (struck down).”

KK Venugopal had made strong arguments before the first bench, with Bobde, on intermediary liability for the Internet and Mobile Association of India (IMAI), a lobby group of internet companies that includes giants such as Google and Facebook. However, he recused himself on ethical grounds when his own former chamber-junior Nariman began hearing the case, recounts Sankaranaryanan.

Who knows whether Venugopal continuing his argument could have helped the internet companies, which did not entirely get the outcome they hoped for: they remain subject to near-unilateral takedown orders from the government without offering them significant protection from liability for third-party content they host under the section 79 “safe harbour” of the IT Act.

Elephants in the room

Several arguing counsel in the case note that the bench was “razor-sharp” and “receptive”, showcasing an “inquisitiveness”, an “understanding of technology” and a “willingness to learn”.

Gupta recounts an instance from when every phrase under Section 66A was being discussed in the courtroom in detail. “An answer which was provided by the (additional solicitor general arguing for the Centre) was a rule of interpretation called the elephant’s rule, in which he stated that the legislature should have the liberty to have a very wide paw - the paw of an elephant - in making such restrictions.”

“The bench displayed its depth of not only law but also of the species of elephants, stating that there were 327 elephants at one point of time and only two remained and maybe the rule which was cited by the ASG was also endangered.”

Choudhary recollects a hearing during which, sitting in the second row, she was shaking her head in disagreement with the ASG as he incorrectly explained a technological term. Chelameswar took notice of her and gave her the opportunity to explain the term and connected-terms, she says. “These two judges – kudos to them – they are not only legal luminaries but the sheer amount of excitement and the eagerness to hear - it was amazing,” she says.

Gupta also notes that the bench did not just “understand technology” but was also “agreeable to hearing counsel and then expressing some query to prod an argument in another area”.

“The patience shown by the judges, the indulgence shown by the judges - nobody could really say that they were not given fair hearings. (The bench) didn’t put pressure on the lawyers to rush through this thing – that was peculiar about this case,” notes Sankaranarayanan.

Petitioner discourse

Singh recollects how the arguments took an interesting turn when senior advocate Shyam Divan and advocate Sai Rajagopal were arguing for the intermediaries’ right to free speech.

“It was really interesting because the court was quite clear (that online intermediaries) do not have free speech (rights),” he says, explaining that the bench raised the point that while newspapers and TV channels have an editorial team in place to moderate, the internet is just “a blank white wall” where people comment and post whatever they want to and this blank white wall does not have the discretion of the newspaper’s editorial staff.

Nundy narrates a similar discussion. “They were saying that businesses did not have a 19(1) right. And there are various nuances to this argument, because there have been judgments which have said that businesses don’t have a right to speech.” In the context of the internet – as Venugopal argued – could result in losing the so-called safe harbour protections provided to intermediaries under Section 69 of the IT Act, she explains.

“So there was a way in which those arguments pushed me to realize that when you’re in the business of speech it must necessarily include a 19(1)(a) right,” adds Nundy. “So, for example, if I have a shop I may not have the right to food but I deal in the right to food. So any reasonable restriction on my right to business in that case must also take into account the impact on business that it has on other people’s right to food.”

Government stand

A “sealed cover”, as arguing counsel and onlookers called the fat file of papers handed by additional solicitor general (ASG) Tushar Mehta to the bench, made an appearance in court before the December 2014 bench as well as the January 2015 bench. According to Tushar, this contained a compilation of extremely offensive material that was available online.

It allegedly included photoshopped pictures of gods and goddesses among other things, confirms Singhal’s arguing counsel Ninad Laud. Mehta declined the petitioners’ request for a copy of the file, asserting that the material was “confidential”.

However, both benches said they did not want to delve into the compilation without hearing legal arguments on the constitutionality of Section 66A, explains Laud, and the bench with Nariman refused point-blank to look at the compilation and allowed one of the petitioners access to it.

“The bench was unwilling to be prejudiced by the extremes,” he comments. Mehta was not reachable for comment by phone and email.

Most politicians, from UPA and BJP alike, came out in support of the 25 March judgment, despite most having previously defended tooth and nail their and others' ability to regulate the unruly online sphere with the law. Hansraj Bhardwaj, who was UPA law minister when Section 66A was inserted into statue books on 22 December 2008 after less than half-an-hour of Lok Sabha debate, but claimed not to have been involved in its passage, accused his colleague P Chidambaram and other politicians of hypocrisy for now welcoming the judgment, despite having defended it in court and in every other forum.

Gupta, in a similar vein, points out that the length of this litigation could have been shorter had Parliament in its last session deleted the challenged provisions, if it had actually felt they were undesirable.

“It is not as if they had to concede in court. Of course the government owes an obligation to defend the existing legislation, but at the same point of time if it feels existing legislation is not good enough, just because it is in challenge before the court, should not stop it from changing it and removing it,” he says.

Another way the government could have helped was to file on time, he points out. “Principally the delay is attributable to the Union of India as well as state governments not filing counter affidavits on time. They did not file it till the final hearing actually started. The counter affidavit should have been filed much prior in time. Not to allege any mala fide against the government, this is just to say that it does not take litigation in the Supreme Court in each matter seriously.”

Delayed as it was, the case and the judgment had a way of setting themselves apart from other matters in the career of lawyers on this one. It may have taken a toll on the day-to-day practice of the many lawyers who worked for free on this case, as one lawyer on it jokes, but its place in all of their careers is best summed up by Laud, who says, “The impact of this judgment really is something that can't parallel any other case that I’ve won so far in my career. This sets it apart.”

A version of this article was first published in Mint. Mint’s association with LegallyIndia.com will bring you regular insight and analysis of major developments in law and the legal world. {tag}link rel=’canonical’ href=”http://www.livemint.com/Politics/VDznbaFeNxSGnLfrYwOBcM/Behind-the-scenes-of-the-fight-against-Section-66A.html#comments_box”{/tag}

Lawyers involved

For the petitioners | For the respondents |

| Shreya Singhal: 2. Manali Singhal,Adv. 3. Saurabh Kirpal,Adv. 4. Ranjeeta Rohtagi,Adv. 5. Ninad Laud,Adv. 6. Abhikalp Pratap Singh,Adv. 7. Mehernaz Mehta, Adv. 8. Gursimran Kaur Dhillon, Adv. | Central government: 2. P.S. Narsimha,ASG 3. Asha G. Nair,Adv. 4. Sarfraz A. Siddiqui,Adv. 5. S.K. Mishra,Adv. 6. Satya Siddiqui,Adv. 7. Rashmi Malhotra,Adv. 8. Gaurav Sharma,Adv. 9. Vidya Sagar, Adv. 10. D. S. Mahra,Adv. |

| Taslima Nasrin: 2. Ankur Talwar, Adv. 3.Liz Mathew,Adv. 4. M.F. Philip,Adv. 5. Kush Chaturvedi,Adv 6. Mr. Aftab Rasheed, Adv. 7. Aftab Ali Khan, Adv. | Kerala: 2. V. Shyamohan,Adv. 3. Shreyas Mehrotra, Adv. 4. Chaitali Yogesh Dhinoja,Adv. 5. Abhishek Kumar, Adv. |

| Internet and Mobile Association of India: 2. Abhinav Mukerji,Adv. 3. J. Sai Deepak, Adv. 4. Savni Dutt, Adv. 5. Rachel Mamatha, Adv. | UP: 2. Abhishek Chaudhary,Adv. 3. Utkarsh Jaiswal, Adv. |

| PUCL: 2. Karuna Nandy,Adv. 3. Apar Gupta,Adv. 4. Pukhrambam Ramesh Kumar,Adv. | Manipur: 2. Ashok Kumar Singh,Adv. 3. Z.H. Isaac Haiding, Adv. |

| Anoop MK: 2. Lakshmi N. Kaimal,Adv. 3. Vikramaditya, Adv. | Andhra: |

| Mouthshut: 2. Mishi Choudhary, Adv. 3. Mr. Prasanth Sugathan, Adv. 4. Shagun Belwal, Adv. 5. Praseena E. Joseph, Adv. | Puducherry: 2. V. G. Pragasam,Adv. 3. S.J. Aristotle,Adv. 4. Prabu Ramasubramaniam,Adv. 5. Mohit D. Ram,Adv. 6. Ravi Prakash Mehrotra,Adv. |

| MP Rajeev Chandrashekhar: 2. Mahesh Agarwal, Adv. 3. Neeha Nagpal, Adv. 4. Shashank Manish, Adv. 5. E. C. Agrawala,Adv. | Maharashtra: 2. Adv. Anirudda 3. P. Mayee,Adv. 4. A. Selvin Raja, Adv. |

| Common Cause: 2. Pranav Sachdeva,Adv. | West Bengal: 2. Shagun Matta, Adv. 3. Saakaar Sardana, Adv. |

| Dilipkumar Tulsidas Shah: 2. Krishan Kumar,Adv. 3. Abhay Naqvi, Adv. | Telangana: 2. Sumanth Nookala,Adv. For M/s. Palwai Venkat Law Associates, 3.Guntur Prabhakar,Adv. 4. Prerna Singh,Adv. |

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first

Para - 3 - it is 24 March 2015*.

Its Apar* Gupta not Apaa Gupta in the table in the end.

That being said, a very nice read indeed!

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first