One of the oldest jokes told by foreign law firm lawyers who often visit India begins with a question about when they think the market will liberalise. “Two years,” the answer will be. “It’s always been two years.”

The joke is funny because it reveals several deeper truths: first, in India, nearly anything can happen within two years; and second, this game of will-it-won’t-it, with respect to liberalisation, has been going on for a long time now.

But I believe things are different this time, although no less complicated.

As we have seen, in cases such as demonetisation and the goods and services tax (GST) for example, this government is strong and confident enough to push through difficult measures that it believes in. And, for a variety of reasons, prime minister Narendra Modi – and finance minister Arun Jaitley, according to several sources – are said to believe strongly that allowing foreign law firms in would encourage foreign investment and foreign investors into India to be more confident, particularly in the infrastructure space where there is a lot of work to be done.

And in the bureaucracy too, the ministry of commerce (and to a lesser extent the law ministry), are keen for reform to take place and are more aware of the issues and roadblocks than previously. At an event in August 2016, a top commerce ministry official rightly said that the government had so far failed to communicate properly with the (possibly) more than 1 million advocates practising in courts: “They feel it is their job that is likely to be threatened. Nobody is competing with their job [or] even looking at that option of competing in the sub courts, municipal courts.” He also mentioned that engagement with the law firm stakeholders was necessary, but stressed that encouraging competition was key to a healthy ecosystem, and floated the idea of a legal ombudsman modelled on other jurisdictions, to improve regulation of the profession.

The hurdles in the government’s path to liberalisation remain real, although domestic groups such as the Society of Indian Law Firms (Silf) – representing a group of law firms that has long resisted liberalisation – has softened in its position last year and is now openly in favour of a staged entry of foreign law firms over the next few years (although it is still possible that this position is primarily a delaying tactic).

It is the Bar Council of India (BCI), that has recently been most publicly opposed to the entry of foreign law firms. But strangely, some of the most important stakeholders in this have never really been asked about what they want. Because what point is liberalisation if no one wants to come?

What do foreign firms want?

According to a survey we sent out to foreign firms late last year, the debate surrounding their entry has long been swirling around the wrong issues, particularly in the case of the resistance of the BCI, which is mainly representing litigating lawyers.

Out of around 60 foreign law firms contacted, we received 16 responses of India practice heads who gave answers to a number of questions, with ratings between 1 and 5 about their interest levels (respectively from “not at all interested” to “highly interested”). Three quarters of respondents were from firms with more than 500 fee-earners, with 63% having more than 11 offices globally. Around 19% of responses came from firms with between 100 and 500 fee-earners. Half were US-headquartered law firms, while two each described themselves as UK/US and European firms.

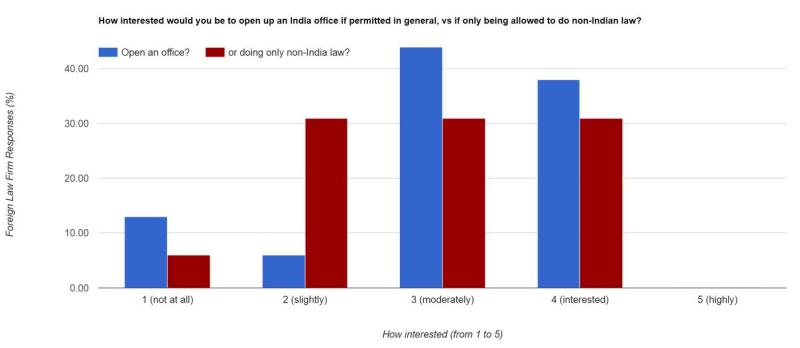

According to this survey, most foreign law firms have not lost their appetite for opening up in India (see chart above).

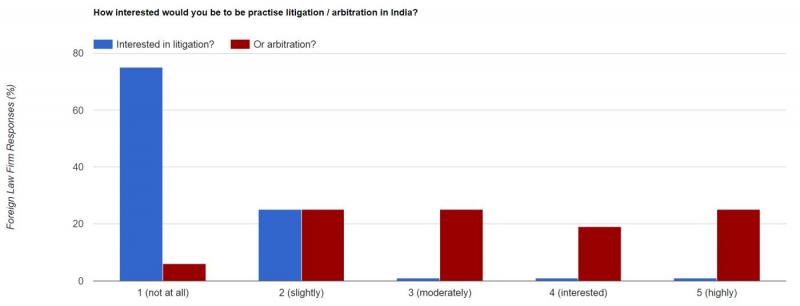

At the same time, the results in respect of whether they would be interested in practising litigation in India were unequivocal: every response gave their interest level at between 1 or 2 on a scale of 5, with 75% responding that they were not at all interested in litigation in India.

That is not surprising: litigating in India is slow and messy, and most foreign law firms’ global clients’ disputes are generally settled through arbitration. That is reflected in the survey results surrounding arbitration, where nearly 70% were interested (see the chart).

How do they want it?

While several different proposals are on the table as to how to eventually regulate foreign law firms, the Law Commission proposals that caused the BCI to call a national strike was mostly silent on this issue, instead leaving it up to the BCI to iron out the details while suggesting largely mechanical amendments to the Advocates Act to change the definition of ‘advocate’ to include foreign lawyers, suitably regulated by the BCI.

As it stands, that would be a bad idea, and having discussions surrounding their entry without a proper roadmap in place will just result in confusion and, considering the BCI’s past track record, in unworkable proposals.

The vast majority of foreign law firm respondents to our survey suggested that they would prefer a Singapore-style model of regulating foreign law firms, with several also voting for the Chinese model. One foreign lawyer said that what was required was a “new regulator with different people” because the “BCI and Indian judges would not be suitable”.

That puts before the government a major challenge. But interestingly, the BCI in its agitation against the Law Commission’s proposals did not mention the issue of foreign law firms as a cause for their grievance, instead mostly focusing on the Law Commission’s suggestion to more strictly impose discipline on the profession (which had literally been the Supreme Court’s primary brief to the Commission), to curtail strikes of lawyers, and to allow non-lawyers and non-bar council members a say in the BCI’s operations.

The BCI’s lack of resistance to the foreign law firms part of the Commision’s draft seems most likely to stem from the fact that the draft envisages the BCI as the key player in the entry of foreign law firms (the BCI’s suspicion that it was being sidelined, had caused it to walk out of liberalisation talks only months before). The draft would create significant opportunity and power for the BCI, but if it is not reformed at all, it might make foreign law firms shudder about being subject to the whims of what has historically been a non-accountable and opaque body.

The alternative would be to create a blank slate with a new body that would sign off on each foreign law firm’s entry and ensure that it complies with restrictions and the local rules, perhaps subject to oversight by the BCI. The big risk in that approach would be that it could alienate the BCI (possibly resulting in new strikes) and risk splitting the regulation of the profession. Though a more effective and strict regulator for foreign lawyers than for domestic lawyers would make sense and be attractive to the domestic market, since domestic regulation is all but defunct.

Where do they want it?

If foreign law firms were to open an office here, 87% of our surveyed sample would first want to do so in Mumbai. Only two foreign firms (13%) out of 15 that responded to the question, put down Delhi as their first choice, and only one opted for Bangalore as a second choice.

All that should be seen in light of a recent piece of news that, albeit overplayed a tad in the national media, amounts at present to the government tweaking its special economic zones (SEZ) rules to allow legal services firms to be hosted inside them. SEZ’s are semi-autonomous free trade zones that have a lot of local leeway to make regulations, possibly even being able to side-step restrictions in the Advocates Act. It is therefore possible that the government intends to soft-launch foreign law firms with a base in SEZs, such as in Gujarat’s GIFT, for instance, which is a place dear to Modi’s heart (and his former constituency in his previous job as chief minister of Gujarat), having the added benefit of encouraging the growth of SEZs.

However, while our survey had been conducted before the SEZ reforms had been announced, being relegated to opening an office in a free trade zone on the outskirts of a city may not be high on foreign law firms’ list of preferences.

What would their strategy be?

Another interesting question is what foreign law firms’ strategy would be, with respect to setting up their India operations. While several of the big firms have so-called ‘best friend’ relationships with Indian law firms already, which could presumably be converted fairly quickly requiring little more than the printing of new business cards and a partnership vote.

But that may also be easier said than done at many firms. The top challenges of opening in India selected by our respondents, included “securing of continued buy-in from global partnerships for India operations”, alongside a host of other factors.

The two top concerns selected by 60% of respondents was that billing rates in India would be too low and that an India operation would likely have lower profitability that the global partnership.

Around half of respondents agreed that the following would be other major challenges:

- risk of litigation and other regulatory hurdles, such as taxation;

- stiff competition from local firms;

- competition from other foreign firms already entrenched in the market;

- continued global buy-in from partnership; and

- maintaining global quality standards.

The good news is, that “scarcity of local talent to hire” was bottom of the list, with only one firm selecting that as a challenge in India, and only a third thought that the costs and overheads of an India operation could be too high.

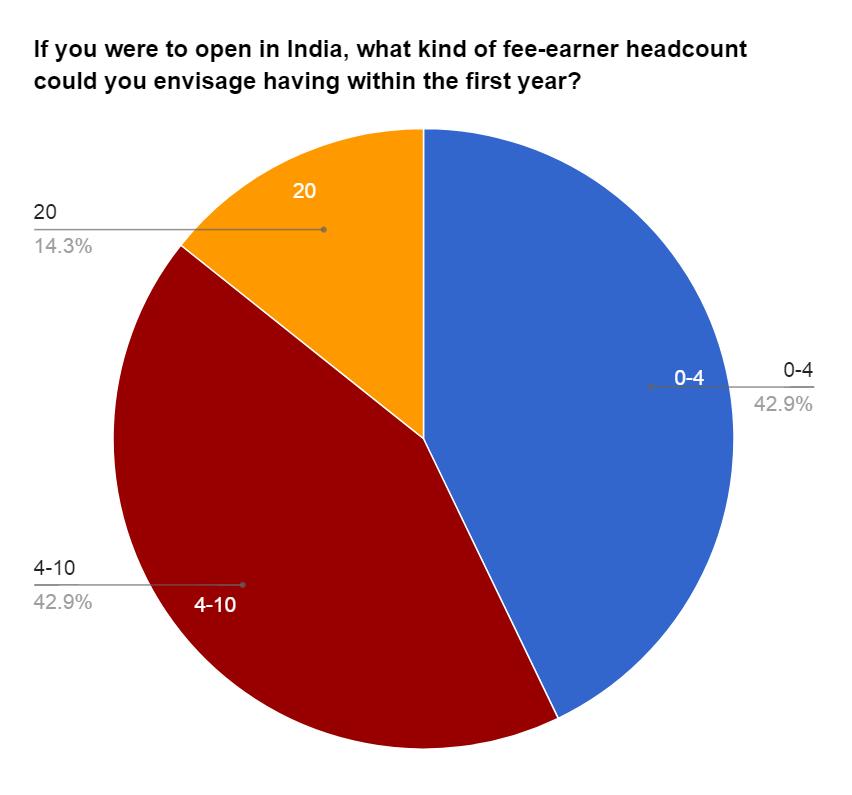

It is therefore unsurprising that most foreign law firms may start slowly and cautiously in India, looking at very conservative headcounts of 10 or fewer fee-earners within the first year (see chart).

Law students, many of whom are hoping that the entry of foreign law firms will suddenly flood the market with lots of new jobs, may be disappointed: the majority of firms surveyed were predicting that they could annually hire one, two and in rare cases perhaps three graduates for their India operations, with only two firms surveyed predicting they might hire five fresh graduates.

Similarly, partners at Indian law firms who might be expecting a gold rush for talent by foreign firms on entry should consider the following: the majority of respondents, 67%, said that for their greenfield operations in India they would transfer partner-level resources from abroad (many foreign firms have been making Indian-origin partners in their India practices for years now, especially in places such as London, Singapore and Hong Kong), while 40% said they would also hire partners from local law firms in greenfield set-ups. With the headcounts indicated, that would translate to no more than two partners in their India offices in the early years. Only 20% of respondents answered that they would look at merging with one or more local law firms.

And when asked whether they were aware of any Indian law firms they could conceivably merge with or take over, 60% responded that they were not aware of any suitable acquisition targets in India at present. Nevertheless, one-third said there were at least several Indian law firms that would be suitable targets.

From the responses, it appears unlikely that the effects of foreign firms’ entry will effect tectonic shifts overnight but that doesn’t mean that their entry won’t be disruptive. While most of the established Indian law firms would be able to easily handle one or two of their high-performing second-rung partners being poached by foreign law firms, it is still likely to hurt their bottom line. And in the longer term, that market will get more competitive, though billing rates will likely inch towards global standards.

And the challenge goes both ways: for foreign law firms to prosper they will have to adapt and crack one of the most complex legal and business environments in Asia, and will need to work closely with domestic firms.

When will it happen?

Several partners who responded were pessimistic, with one predicting five years and some even saying that it would not happen in this lifetime, due to resistance from the entrenched Indian law firms.

But sentiments and pressure has increased to greater levels than ever before. In a recent survey of 87 Indian general counsel (GCs), an overwhelming 89% said they would like to see relaxation of regulations to allow the entry of foreign law firms, and 87% said it would be good for the Indian market as a whole. And although the GC community has historically not been very vocal at a policy level about the issue, that too is changing.

The Indian Corporate Counsel Association (ICCA) - a representative body of Indian GCs - had been closely involved in the ministry-led talks with stakeholders on liberalisation. In collaboration with a legal industry consultant, the body submitted a very thorough and quite workable roadmap for staggered foreign direct investment (FDI) into the legal profession, ratcheting up gradually from 26% in the first years, while also making provision for continuing legal education, liability insurance and other vital reforms.

Notwithstanding all the above complexities and the web of competing demands, whenever asked for my personal opinion, I will stick to the traditional, safe and slightly amusing answer: anything is possible in India in two years.

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first

www.livemint.com/Companies/RJMJ0oL2XuDF8A2TTBuKWJ/RIL-to-invest-25-million-in-Israeli-startup-incubator.html

However, since transactional lawyers at Indian law firms are themselves under scrutiny with regard to their right to practise as "advocates", most litigating lawyers will be unwilling to compromise their right to practice by joining foreign firms, so they will have to be engaged as off-counsel or on case-to-case basis.

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first