Experts & Views

John Doe orders: The Balancing Act between Over-Blocking and Curbing Online Piracy

The Bombay High court recently passed a John Doe order laying down a set of safeguards to minimise over-blocking. The Delhi High Court on the other hand ordered blocking of 73 websites for showing “substantial” pirated content. This blog post traces the history of John Doe orders in India, their impact on free speech and evaluates the recent developments in this area.

John Doe Orders and their Impact on Freedom of Speech

John Doe or Ashok Kumar orders usually refer to ex-parte interim injunctions issued against defendants, some of who may be unknown or unidentified at the time of obtaining the order. Well recognised in commonwealth countries, this concept was imported to India in 2002 by an order passed against unknown cable operators to give relief to a TV channel in the case of Taj Television v. Rajan Mandal. The trend to issue John Doe orders to prevent piracy picked up pace in 2011 when the Delhi High Court passed a series of such orders. Since then, a stream of such orders has been passed authorising copyright holders to take action against unknown persons for violation of their right against piracy (in the future) without moving to the court again. The orders authorise copyright holders to intimate ISPs to take down the allegedly violating content. In 2012, the Madras High Court clarified an earlier order (which had resulted in blocking of a number of websites) stating that it pertained only to specific URLs and not websites. Despite this, John Doe orders for blocking of websites are common place.

John Doe orders are passed as ex-parte orders due to paucity of time and the difficulties in identifying defendants in such cases. However, these orders threaten to impair freedom of speech online due to a host of problems. First, these orders are given on the basis of a mere ‘possibility’ of piracy with no requirement to establish piracy before the court post blocking. This paves the way for negligence or misuse of the power to take down content by copyright holders. Second, these orders are usually passed on a minimal standard of evidence on the word of the plaintiff without sufficient scrutiny by the court of the URLs/websites submitted. Third, they do not require the copyright holders or ISPs to inform the reasons for blocking to the persons whose content is taken down – leaving almost no recourse to those whose website/URL may be blocked mistakenly. Fourth, the burden of carrying out these orders falls on the ISPs who block the websites/URLs erring on the side of caution.

The absence of scrutiny and the lack of safeguards lead to over-blocking of content. Users who suffer as a result of these over-broad orders often lack the knowledge or means to overturn these orders resulting in the loss of legal and legitimate speech online. Further, without any requirement for reaffirmation of the blocks from the court –private parties (the copyright holders) themselves become adjudicators of copyright violations hampering the rights of users affected by these orders.

Instances of over-blocking as a result of these orders are many. In May 2012, as a result of an order by the Madras High Court a range of websites were blocked including legitimate content on video sharing sites like Vimeo. In 2014, the Delhi High court had issued a John Doe order mandating blocking of 472 websites including Google documents in wake of the FIFA world cup. Many questioned such widespread blocking under the mere assumption that the websites would support pirated screening of the FIFA world cup especially without verification by the courts. The order was later tailored down.

The Bombay High Court Order

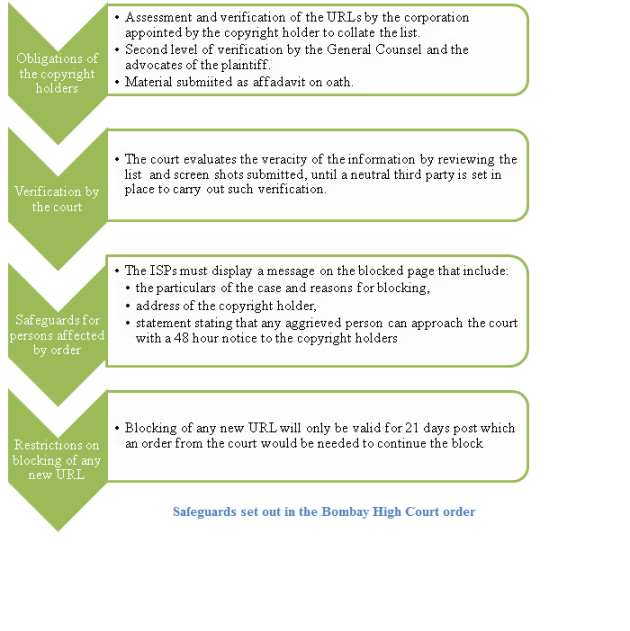

The jurisprudence regarding John Doe orders saw a shift when Justice Patel from the Bombay High Court took a huge step forward with his order dated July 26 2016 for the movie Dishoom. This order recognises both the harms of piracy and the adverse impact of John Doe orders on unknown defendants as it attempts to balance the ‘competing rights’. The order lays down a multi-tier process to minimise the negative impacts of John Doe orders and tailors down blocking from entire websites (except in certain conditions) to URLs (see chart below).

The order sets in place a mechanism that provides for selective blocking of content, verification of the list of URLs as well as safeguards for the unknown defendants. Such a mechanism helps ensure that freedom of speech online is not trampled in the fight against online piracy.

The Delhi High Court Judgement

The Delhi High Court in its judgement (not a John Doe order) dated July 29 2016 blocked 73 websites in a case regarding live streaming of pirated videos of cricket matches. While some lauded this judgement for its contribution to India’s fight against piracy, it is important to understand its many failings.

The high court blocked the websites on a ‘prima facie’ view of the material placed before it by the plaintiffs that the websites were entirely or to a large extent carrying out piracy. However, it remains unclear as to what standard was used by the court to determine the extent of piracy. Further, complete blocking of websites would encroach upon the right to carry on business and freedom of expression of the other party therefore the standard for placing such a restriction must be high and well defined. This was recognised by Justice Patel in the Bombay High Court order – where the court clarified that while there is no prohibition on blocking of entire website there is a need for a ‘most comprehensive audit or review reasonably possible’ to establish that the website contains ‘only’ illicit content.

Even though the judgment of the Delhi High Court is against 73 named defendants, the order was passed merely on a prima facie review of material laid before it which displays a lack of system for verification. A mere prima facie review of material is insufficient as a third party whose website is mistakenly blocked would suffer unnecessarily. With no directions to put out a notice of information to the defendants – he/she may not even be aware. Thus, the Delhi High Court order suffers from various problems that pave way for over-blocking of content. The judgement also places an unfair burden on the government and raises questions regarding the role of the intermediary– which has been articulated in detail in a post by Spicy IP here.

Questions for the Future

These developments raise a number of issues for the future – the most prominent being the need to reconcile the differing legal developments on the issue of online piracy across India. Further, there is a need for the courts to be more sensitive to the plight of unknown third parties while passing John Doe orders following the lead of Bombay High Court.

Two particular issues come to light amongst this mess. First, the need to develop a standard while blocking of complete websites that is sufficiently high to prevent misuse and over-blocking. Second, to develop a neutral body that can verify the lists for blocking on behalf of the courts – that ensures sufficient checks in the system while keeping in mind the paucity of time in these cases. However, any such body must possess the technical know-how to understand how these lists are put together and other related issues. The lag between technology and law is very real- as correctly pointed out by Justice Patel- and these small steps will go a long way in bridging these gaps.

(For some more reading on this issue you can look at a piece published in the Mint here and for a more detailed reading on the Bombay High Court order you can read the Spicy IP post here)