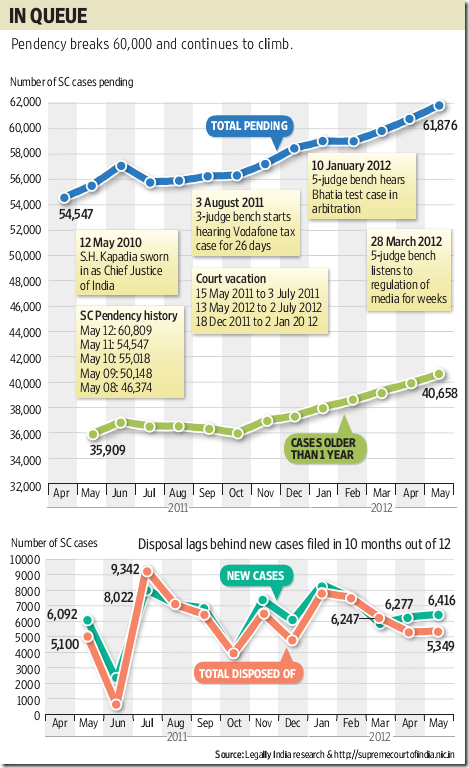

By May 2011, the number of pending cases at the apex court had indeed decreased by almost 500 to 54,547. This reversed a trend that had begun in 2008, when 46,374 cases were pending and then steadily had grown by around 10% year-on-year.

In the second year of his term, those gains have been more than just erased: the tally of pending cases in the Supreme Court has exceeded 60,000 for the first time in its history. At May end it stood at 61,876, 13.4% more than the May 2011 total.

The number of unresolved cases older than one year has increased to 40,658 from 35,909.

“When you start a process it goes with a momentum that is a much higher one,” said senior advocate Pinky Anand.

Kapadia started off well and the systems he introduced made a difference in the speed of administration and pending cases, she said. “But we manage to dampen systems one way or another (and there is) obviously a lot of opposition to some dramatic changes— somebody is always benefiting from the old system.”

There is also a personnel issue to be considered.

The last 12 months have seen several retirements at the Supreme Court. Ten justices reached their retirement age of 65 or otherwise left—starting with justice B. Sudershan Reddy in July 2011, justice Markandey Katju and justice R.V. Raveendran in September and October respectively, and ending with justice Dalveer Bhandari, who became a judge at the International Court of Justice after April 2012. There have been more retirements in less than one year than there have been in the three years before.

Reddy’s departure in July was also preceded by an 18-month period when not a single judge retired after justice Tarun Chatterjee did so in January 2010.

Managing this unusually large exit of experienced judges and replenishing the ranks falls to the chief justice and a collegium of judges, as so many other things do. While Kapadia’s collegium managed to appoint eight new judges in 2010-11, this still puts the Supreme Court bench strength, including himself, at 27, two short of where it was at the start of 2011, and four below its sanctioned maximum strength of 31 sitting judges.

Although retiring judges often have a habit of wrapping up cases and delivering judgements that may have been on their plate for a while, helping clear the case mountain slightly, the acclimatization of new judges and the handover period can add up to an administrative nightmare. While the debate about further increasing the retirement age of judges continues—“a judge is not a football player”, justice Asok Kumar Ganguly said after he retired in February—the timing of those departures and how much they coincide comes down to luck of the draw.

There seem to be other fundamental issues at play as well. Decreasing the pendency of cases in the apex court is no doubt a difficult task, acknowledged Anand, but she added that “the system itself has certain inbuilt deficiencies”.

“One very strong feature is that every matter seems to come to the Supreme Court,” she said.

Senior counsel K.K. Venugopal noted that the Supreme Court has effectively become a court of appeal, correcting errors of facts or law of lower courts. “This is not the proper function of the apex court of a country. And with the large population and enormous litigation starting with the subordinate courts or the high courts, the Supreme Court gets bogged down with huge arrears.”

Indeed, the statistics show that the number of fresh cases that reach the Supreme Court is huge—8,368 in January alone. There were only two months in the last year in which the court managed to dispose of more cases than flowed in (in July 2011, the month Reddy retired, 9,342 cases were disposed of by the 29 judges: more than 300 per judge, which equates to an average of more than a dozen cases dealt with per day in July’s 25 court working days).

As it stands, the Supreme Court has to keep fighting that wave of incoming cases and perceived injustices meted out by the lower courts just to stand still on the pendency count, while trying to answer questions of constitutional importance too along the way.

Every Monday and Friday at the supreme court are so-called “miscellaneous days”, or days on which all the judges hear fresh cases and decide which to admit into the queue for a “regular hearing” and which ones should be “dismissed” forthright.

Miscellaneous mornings are usually a hectic flurry of advocates, petitioners, hearings and dismissals, while a few courts might hear special cases in the afternoons. On Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays, judges hear the actual cases, full-time. In regular hearings where the court has to answer a substantial question of constitutional law (the original raison d’etre of India’s Supreme Court and the top courts of most countries), the case will usually be heard by the constitution benches convened by the chief justice and consisting of five or more judges.

The cases without constitutional significance are usually heard by two judges.

Other complex or technical cases such as the Vodafone tax dispute, for example, may also come up before a three-judge bench. Sometimes this happens by design or the reason can be as prosaic as not being able to find one of the 15 court rooms free for hearings. Constitution benches and key cases effectively occupy several judges for months at a time, preventing them from disposing of more routine cases on regular hearing days.

“It’s definitely to do with the constitution benches,” said additional solicitor general and senior advocate Indira Jaising about the reason for the increase in pendency, citing the right to education case that was heard for two months and more by a bench of three, the Vodafone-Hutch tax case that was heard for two months by Kapadia and two others, and the 2G case that kept two judges busy for nearly four months in total.

“In an ideal system there has to be a system of prioritizing of cases and you need to have a rational basis on which you hear certain cases before you hear other cases,” said Jaising. “The prioritization is not always visible and quite often cases which are high profile do get priority.”

Some advocates and sections of the media, meanwhile, expressed puzzlement when a five-judge-bench headed by Kapadia spent several weeks since 28 March examining whether and how the media’s reporting of court cases should be regulated. But the judgements that emerge from such constitution benches are usually the ones that make the big headlines, and often, as in some of the above matters, they can have huge economic or social repercussions.

The difficulty is that the chief justice and the Supreme Court’s balancing act between disposing of the old routine appeals, and keeping up with the new, while continuing to preside over the revolutionary, has become nearly impossible. In theory, a constitution bench can also have an effect on pendency.

The Bhatia International five-judge-bench that held 10 days of hearings in January was formed to settle the law relating to Indian courts’ role in foreign arbitration awards, an area that has long been at the heart of a few other currently pending cases.

One lawyer relates how several thousand pending cases are connected to the jurisprudence of the five-judge constitution bench in the 2006 Jindal Stainless Steel case over whether states can impose an entry tax on goods. Then, in 2008, a two-judge bench (also including tax-expert Kapadia before he became chief justice) in the Jaiprakash Associates case decided that the law relating to entry tax was not settled after all, and that another constitution bench should look at the matter again. This time, in order to have the power to overrule the five judges of the previous bench, it will have to be a nine-judge bench. It is unsurprising that to date it has proved impossible to schedule nine judges to sit together and pay concerted attention to this complex case, without being interrupted by a retirement or stalling other matters.

Indeed, due to modern-day time constraints, constitution benches have actually become a relative rarity. “While the (Supreme Court of India) averaged about 100 five-judge or larger benches a year in the 1960s, by the first decade of the 2000s, this had decreased to about nine a year,” noted February 2011 research published in the Economic and Political Weekly by Nick Robinson and others. “Viewed in this light, despite deciding about 5,000 regular hearing cases a year in the 2000s, the Indian Supreme Court arguably produces less jurisprudence involving substantial questions of constitutional law than a court like the United States Supreme Court, which wrote just 72 judgements in 2009, but whose cases often involved such questions.”

“This is not a simple question which has a straightforward answer,” said senior advocate K.K. Venugopal. “Many committees have sat on this issue for decades and, as we have seen, nothing has worked so far.”

Opinion: Are there any possible solutions in the pendency project?

There’s much that contributes to the rush of cases in the country’s apex court. A litigant who gets beaten in the high court has nothing to lose, except money paid to lawyers, by rolling the dice again in a Supreme Court appeal, because nobody can predict the result with any certainty.

In fact, in disputes of significant value, the inevitability of a Supreme Court appeal is usually factored into the case strategy and total cost right from the start.

The high-profile media coverage for some Supreme Court cases adds to the queue.

“Everyone wants to take a chance,” says Pravin H. Parekh, president of the Supreme Court Bar Association (SCBA).

A number of lawyers suggest the solution is for the court to frame far stricter guidelines about which types of cases it will hear. At the moment, this depends on the judge hearing the appeal.

Counsel K.K. Venugopal makes another point: “We find the high courts commit serious errors of facts and of law in their judgements. To shrug one’s shoulders and allow the case to rest at that level would, therefore, be doing an injustice to the system.”

He proposes four new national appellate courts that have exclusive jurisdiction to review certain categories of cases where “grave errors have been committed by the high court or gross injustice has resulted”.

“There are over a hundred such categories which now come before the Supreme Court but which should end finally with the court of appeal so that the Supreme Court is left free to decide every year about 2,000 cases or so which would involve constitutional issues or issues of great national importance.”

Parekh disagrees with this proposal. “That will add to the delay,” he argues. “If the Supreme Court wants to interfere, it will interfere. An appeals court will not stop them.”

Arguably as important is who happens to be the chief justice. Some may get serve a few months in the post before turning 65, while others may have a longer term during which they can try to achieve longer-term goals.

Chief Justice S.H. Kapadia will retire this September, and the mantle will pass to Altamas Kabir until July 2013. Whether Kabir or other successors will continue Kapadia’s reforms and maintain the same system is anyone’s guess.

“I believe that the judges of the Supreme Court of India should sit together every weekend once and have brainstorming sessions so that they may be able to evolve solutions,” argues Venugopal. Any solutions the judges come up with could then be passed on to the central government. “It is the apathy of the government which is the real reason for the lack of progress in clearing the arrears.”

Of course, perhaps the last thing the government wants is an even more powerful, efficient and activist Supreme Court.

But the government’s role can’t be ignored: it is the single biggest litigant in the Indian courts, often because bureaucrats are wont to exhausting every appeal. The previous law minister, Veerappa Moily, while unveiling a national litigation policy in June 2010, admitted that this was the case and created a framework to decide which cases should be appealed and which ones shouldn’t.

Since Salman Khursheed became law minister, the profile of the national litigation policy has decreased. But attorney general Goolam E. Vahanvati—the government’s top lawyer—says that the national litigation policy is still being implemented and constantly revised. “We have substantially reduced our filings,” he says, although he was unable to provide precise figures at the time of going to press.

Perhaps what really needs to happen is a dispassionate look at the entire problem, backed by empirical research, to find fresh solutions rather than relying on the existing structure.

For example, could academic or private-sector think tanks or consultants with experience in logistics and management not recommend exactly how delays occur, where the bottlenecks are and how they should be avoided, as they’d do with a company? Could a highly paid and meritocratic cadre of Supreme Court administrators, whose sole purpose is to ensure the smooth running of the court without having to change jobs every year, make a difference?

While there is no shortage of ideas, there is an inherent, and understandable conservatism about changing the formula at India’s most respected court, which has functioned so well in many other regards. But perhaps it is time to acknowledge that what has been tried so far in tackling case pendency is not working, and to start being more radical.

These articles first appeared in Mint. Legally India has an exclusive content partnership with Mint, which will feature the latest legal news and analysis every fortnight on Fridays in its print and web editions.

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first

Also one could think of imposing monetary costs on AoR's who file cases where alternative remedies are possible or otherwise other restrictions which have been read into Art. 136 or the case appears frivolous. One often comes across cases which read like this:

Dispute over property arises in 1990. TC dismisses the suit in 1999. First appeal to District Court, dismissed in 2003. Second appeal to HC, dismissed in 2010 as containing "no substantial question of law". Hence an SLP in 2011. Such cases merely clog up the system as being chance/luxury litigation and play havoc with the lives of litigants and are often due to the lack of honest advice by lawyers.

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first