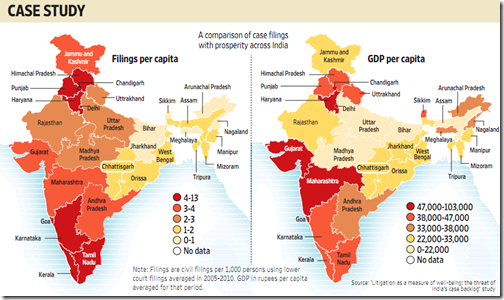

Litigation and prosperity in India, in fact, are linked positively, said the research paper titled Litigation as a measure of well-being: the threat of India’s case backlog. Higher per-capita gross domestic product (GDP), and higher human development index and urbanization lead to more lawsuits per person, it said.

The study found that more prosperous states in India have higher civil litigation per capita, and legal cases within these prosperous states might have plateaued (or decreased) in recent years because of a judicial backlog.

“By emphasizing the relation between civil litigation rates and improved human well-being, we challenge the dogma that increasing litigation rates should be regarded as evidence of a malfunctioning society,” Theodore Eisenberg and Sital Kalantry of Cornell University, New York, and Nicholas Robinson from the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi, wrote in their report.

“We demonstrate that Indian states with higher civil litigation rates also generally have higher GDP per capita. In fact, a state’s Human Development Index (HDI) score correlates even better with higher litigation rates,” Robinson said by email. “In other words, high litigation rates in India are a sign of prosperity and overall well-being, not a sign of societal decay.”

Data from 2005 to 2010 of cases from across India’s lower courts as well as economic and non-economic factors of well-being demonstrate this phenomenon, the study said. “We present evidence that India’s enormous case backlog may be deterring potential litigants from filing claims,” said the paper.

The judiciary in India, while independent of the government, is controlled top-down by the Supreme Court of India, through its collegium, administering appointments of its own judges and the judges to the 22 high courts, among other functions. Below this appellate tier are about 600 district and lower court complexes in India, presided over by about 14,000 judges, which is largely the focus area of the study since they are usually the first instance of filing a lawsuit.

The justice delivery system’s status as a trusted institution is under threat because of a strong correlation between the growing case backlog and a decline in the number of lawsuits.

India’s case backlog ratio has increased 28% from 1977 to 2010. The study argues this might not be the failure of individual judges, but a malaise on an institutional level because of poor infrastructure (fewer courts also) and vacancies on the bench. Another reason attributed to the decline in litigation is corruption, which injects a lack of predictability in the system.

The measure of prosperity used by the authors is primarily per-capita net state domestic product, which is GDP minus depreciation on capital goods. They have also factored in HDI (including lifespan) and population density, or urbanization.

However, the study “does not imply that filing more lawsuits will increase societal well-being”, say the authors, who encourage a “reasonable” interpretation of the findings. In fact, the causation is opposite—higher well-being leads to more litigation—they argue.

The authors caution that the current problem with litigation in India appears to be that there are too many delays in the system. “India’s challenge is not that too many cases are filed, but that too few are timely adjudicated. Its litigation rate, by world standards, is not high,” the study said. “The judiciary, though in increasing demand as the country prospers, could threaten India’s prosperity if it cannot accommodate demands for its services.”

This article first appeared in Mint. Legally India has an exclusive content partnership with Mint, which will feature the latest legal news and analysis every fortnight on Fridays in its print and web editions.

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first

threads most popular

thread most upvoted

comment newest

first oldest

first